ABSTRACT

This paper provides a systematic review of research on metabolomics and peptidomics in cocoa, focusing particularly on compounds that influence flavor formation during postharvest processing. Special emphasis is placed on peptides and carbohydrates, which play a critical role in flavor quality. The systematic review involved searching the Scopus and Web of Science databases using equations, followed by merging the results into a unified dataset. A scientometrics analysis was conducted to evaluate scientific productivity across various parameters. Theoretical insights were illustrated using the Tree of Science framework to clarify core contributions. Key findings highlight that omics methodologies are pivotal for understanding the cocoa metabolome and peptidome, contributing to the establishment of robust databases of flavor precursors. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to identify specific metabolites that directly influence sensory attributes and to determine essential metabolites and optimal conditions for the development of high-quality products. Moreover, evaluating how postharvest and agro-industrial processing conditions affect quality biomarker modulation in order to maintain consistent sensory quality. This review uniquely contributes by introducing the innovative application of the Tree of Science methodology to cocoa research, offering a structured scientometric perspective on the evolution and emerging trends in cocoa metabolomics and peptidomics. Furthermore, the analysis of key flavor-related metabolites presented here serves as a valuable resource for optimizing cocoa flavor quality through targeted postharvest interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Chocolate is one of the most consumed products globally and is mainly valued for the sensations that consumers experience in the face of the complexity of its exquisite flavor.[1] The flavor quality is influenced by the interaction of multiple factors such as cacao genotype, environmental and growing conditions and the postharvest transformation process.

Considering the flavor, two cocoa classes are distinguished worldwide: The Fine Flavor Cocoa (FFC) characterized by the cocoa derivatives that develop specialty aromatic notes as florality, fruity, nutty and caramel and on the other hand, bulk cocoa, which exhibits a basic cocoa flavor without any differentiating aroma when processed in cocoa derivatives.[2]

Driven by new consumer trends favoring chocolates with higher cocoa solids content and with specialty flavor characteristics, the Fine Flavor Cocoa (FFC) market has exhibited a significant growth.[3] This market has advantages over the bulk cocoa market, higher profitability and price stability. Therefore, participating in this specialized market is a great opportunity, nevertheless, to achieve it, cocoa with specialty flavor characteristics should be produced.

The postharvest processes critical influence flavor quality by inducing physical and chemical transformation in cocoa seeds as they are converted into cocoa beans and eventually chocolate. During the transition from seeds to beans, fermentation and drying are the key stages, whereas roasting is crucial during chocolate production.[4] During these processes, chemical components of the seeds such as proteins and carbohydrates are transformed into low weight molecules, including peptides, free amino acids and reducing sugars. These compounds, known as flavor precursors, participate in Maillard reactions during roasting, resulting in a complex matrix of volatile compounds. Together with non-volatile compounds such as phenolic compounds and methylxanthines (e.g., theobromine, caffeine, theophylline), they define the sensory profile of chocolate.[5]

As the metabolomic fingerprint is significantly affected by the postharvest processing variables, understanding the cocoa metabolome becomes an important way to explain the flavor formation and its relation to cocoa quality. This information can contribute to control and systematize the postharvest transformation process of cocoa, based on the desired quality sensory characteristics in the final product, especially when process biomarkers associated with specific quality attributes are known and can be used to follow the process behavior in terms of the quality.[6,7]

Other reviews about the flavor formation and the influence of the transformation process on the cocoa quality, have been written in the last decade.[2,4,5,8,9] However, according to the literature search, this is the first scientometrics analysis related to the cocoa metabolomics and peptidomics in cocoa.

Consequently, the present review aims to identify (i) identify and discuss the key metabolites, particularly peptides and carbohydrates, that significantly influence cocoa flavor development during postharvest processing; and (ii) reveal emerging research trends and pivotal contributions in cocoa metabolomics and peptidomics through scientometric analysis, employing citation networks, clustering methodologies, and the Tree of Science algorithm.[10,11]

Accordingly, this review and scientometric analysis seek to answer two specific questions:

First, what are the key metabolites influencing cocoa flavor during postharvest processes?. This question guides a detailed discussion on the biochemical transformations occurring in cocoa seeds, focusing on peptides and carbohydrates as essential precursors for flavor development.

Second, how do scientometric tools reveal emerging trends in cocoa metabolomics and peptidomics?. Through scientometric analysis, this review aims to identify central themes, influential research clusters, and the evolution of knowledge in cocoa science, facilitating the recognition of current trends and future research directions.

The citation network was made up of 4,021 papers from the records of the search and the cited references of each paper. Also, we identify the perspectives in which metabolomics and peptidomics were applied in the study of Theobroma c. using the modularity algorithm in the citation network. Finally, traditional metrics such as production per year, the most productive journals and the co-author network of researchers were also performed.

Hereinafter, this manuscript is divided into two sections. The first section describes the methodology of systematic literature review and scientometrics analysis. And the second section presents the theoretical discussion of metabolomics and peptidomics in cocoa postharvest processes and its influence in quality.

METHODOLOGY

Search equation

The search equation was performed in Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases following two equations searches and indexes SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, ESCI. The first equation was “Topic: (Cacao OR Cocoa OR Theobroma) and Topic: (metabolomic* OR peptid*)” and the same equation in Scopus in title, abstract and keywords. The second equation: “Topic: (Cacao OR Cocoa OR Theobroma) and Topic: (sugar* OR carbohydrate*)” in both WoS and Scopus. For the first equation search, 284 records were downloaded with the cited references in a plain text format from WoS and 385 records from Scopus in bibText format with all records and cited references. For the second equation, 1023 records were downloaded with the cited references from WoS and 1981 from Scopus (Table 1).

| Parameter | Web of Science | Scopus |

|---|---|---|

| Range | 2000 – 2024 | |

| Date | February 13, 2024 | |

| Document type | Papers, books, chapters, conference proceedings, reviews. | |

| Search field | Title, abstract and keywords | |

| Equation 1 | (metabolomic* OR peptid*) AND (cacao OR cocoa OR theobroma) | |

| Equation 2 | (sugar* OR carbohydrate*) AND (cacao OR cocoa OR theobroma) | |

| Results equation 1 | 284 | 385 |

| Results equation 2 | 1023 | 1981 |

| Total | 1307 | 2366 |

All records and cited references were merged into a single dataset using the R package “tosr” (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tosr/index.html) which facilitates the integration of primary records with their cited references. By combining the extensive Scopus and WoS databases, we accessed over 150 million records of scientific records, enabling an overview of research related to cocoa flavor precursors.

A PRISMA diagram[12] (Figure 1) illustrates the paper selection process employed for this review. The preprocessing stage, essential for the subsequent data analysis, was executed using R scripts developed by Core of Science (https://github.com/coreofscience, accessed on May 13, 2024). This step involved extracting key information from references, handling missing values, and preparing the dataset for analysis.

Figure 1:

PRISMA diagram. Document selection process.[12]

Scientometrics analysis

We conducted a scientometric analysis to quantitatively examine various scientific data, such as annual scientific production, average citations per year, relevant sources, author productivity and co-citation analysis, among others. This pipeline was designed to start from general metrics and gradually progress toward more specific insights. The scientific annual production included the results of WoS and Scopus separately as well as total publications per year in the dataset and the total citations. Moreover, country production, journal contribution and co-authorship were visualized through tables and network graphs.

Tree of Science (ToS)

References and cited records were classified and prioritized using Tree of Science (ToS) methodology, an open-source approach for literature mapping based on citation network analysis. This method categorizes papers into three groups according to network topology,[10,11] roots, trunk and leaves. Roots represent classical papers, the trunk is the bridge between the classical and the most recent academic literature and the leaves show the newest papers that exhibit a higher connection with the trunk and root.

The main sub-areas or perspectives were extracted from the network citation using the modularity class algorithm,[12] the main three clusters were extracted from the network citation to identify different perspectives of this area of knowledge.

Moreover, the open-source software Gephi[13] was used for the data visualization and to apply the modularity class algorithm. The full code used for data preprocessing, network construction, and visualization is openly available at: https://github.com/coreofscience/tosr.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Scientometrics analysis

Search equation

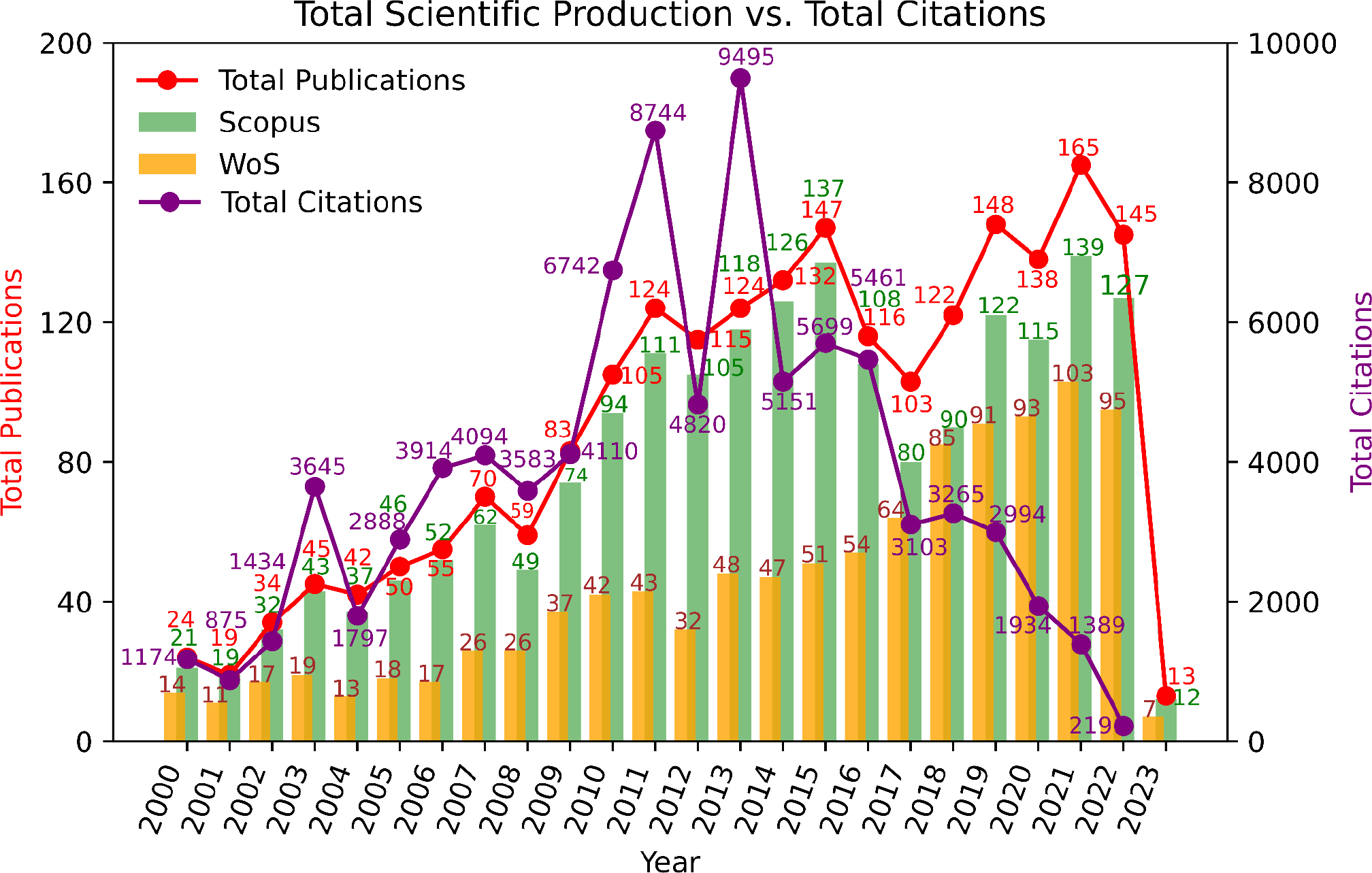

Figure 2 shows the documents produced in the last 2 decades related to metabolomics, peptidomics and sugars in cacao. Scientific production in cocoa metabolomics and peptidomics showed a marked increase between 2000 and 2015, representing 62% of the total output. After a brief decline, publication rates stabilized, reaching a peak again in 2021. This pattern reflects an initial phase of rapid growth followed by a consolidation period. Key contributions during these stages, such as the identification of diketopiperazines by Stark and Hofmann,[14] and the influence of yeasts and starter microorganisms on the bean metabolome and sensory profile.[15–19] Significantly advanced the understanding of flavor precursor metabolites. In this period important contributions emerged on cocoa peptidome,[6,7] as well as sugar contribution on sensory profile.[20] The number of citations followed a similar pattern until 2013, with a peak of 9,495 citations in that year, followed by 8,744 citations in 2011. The most cited article is a comprehensive review of the different groups of compounds and foods,[21] highlighting a significant research sub-line focused on the impact of these metabolites (peptides and sugars) on humans. On the other hand, the most cited article related to metabolites and the sensory quality of chocolate is by Ho et al.,[18] that was discussed at the beginning of this section.

Figure 2:

Scientific production.

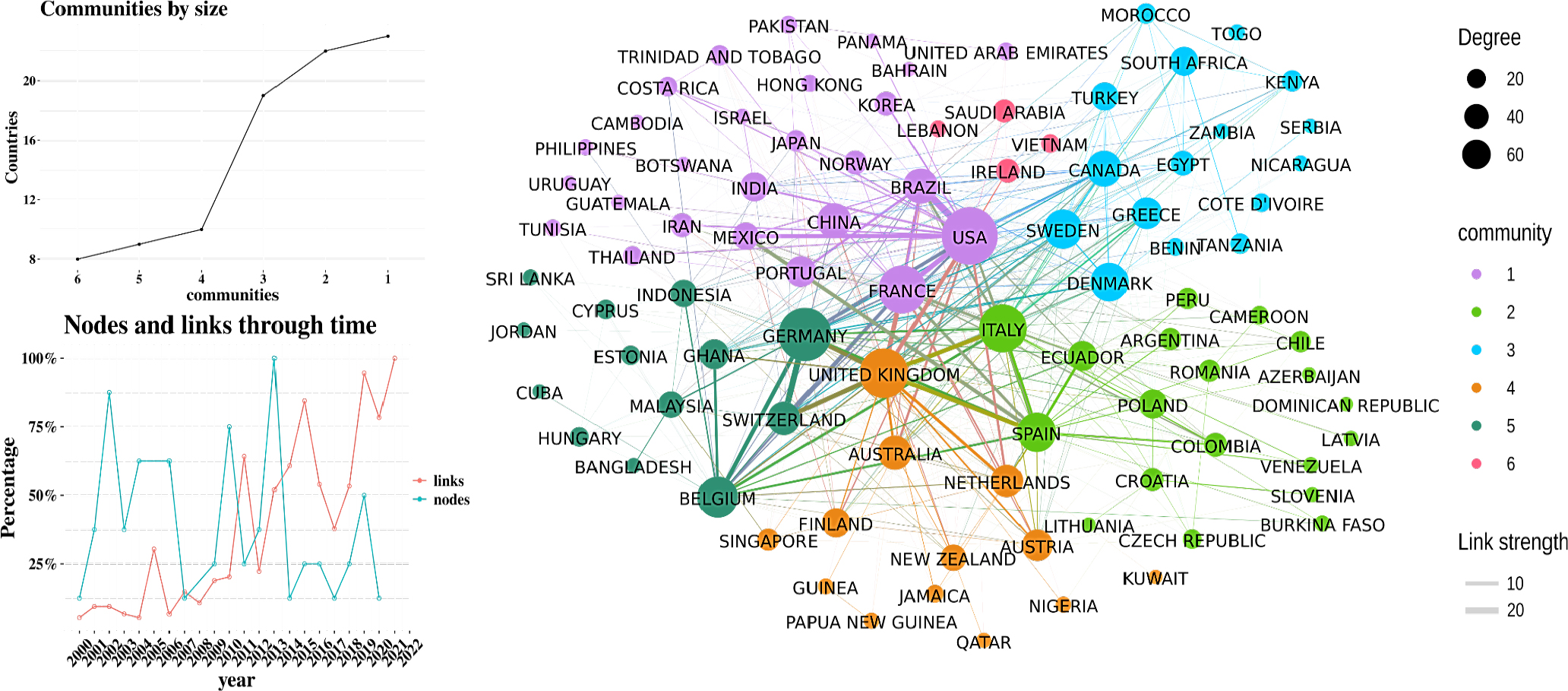

Country network

Although associating cocoa metabolites with specific sensory profiles remains complex, significant research efforts are concentrated in a few countries. Approximately 1,500 documents and 45,600 citations come from just 10 nations. Notably, major cocoa producers like Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana contribute little to academic production, while countries like Indonesia and Brazil, and major chocolate consumers such as Germany and the United Kingdom, lead in research output. These findings highlight that scientific productivity in cocoa metabolomics and peptidomics is more aligned with research infrastructure than with cocoa production or consumption levels.

In the USA, there have been 393 papers in prestigious scientific journals. Out of these 393 documents, most of the documents are published in Q1 journals near to 53% (207), 12% (47) in Q2, 3.6% (14) in Q3, 1.5% (6) in Q4 and near to 30% of the total publication is in journals with no category (Table 2). Within this group of articles, one noteworthy publication is Lonchampt and Hartel[22] with 185 citations, which outlines the different process mechanisms by which fat bloom forms in chocolate manufacturing and its impact on the sensory profile.

| Country | Production | Citation | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | No category | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 393 | (14,79%) | 14828 | (19,60%) | 207 | 47 | 14 | 6 | 119 |

| Brazil | 258 | (9,71%) | 5209 | (6,88%) | 96 | 58 | 29 | 6 | 69 |

| United Kingdom | 183 | (6,89%) | 8177 | (10,81%) | 81 | 19 | 2 | 2 | 79 |

| Germany | 148 | (5,57%) | 4333 | (5,73%) | 79 | 16 | 14 | 0 | 39 |

| Spain | 117 | (4,40%) | 3058 | (4,04%) | 70 | 16 | 7 | 6 | 18 |

| Italy | 98 | (3,69%) | 4542 | (6,00%) | 60 | 14 | 7 | 1 | 16 |

| France | 93 | (3,50%) | 2486 | (3,29%) | 51 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 19 |

| China | 72 | (2,71%) | 1243 | (1,64%) | 35 | 13 | 2 | 7 | 15 |

| India | 72 | (2,71%) | 1361 | (1,80%) | 21 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 26 |

| Indonesia | 66 | (2,48%) | 363 | (0,48%) | 8 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 38 |

As for Brazil, the distribution of the publication in the quantiles is more homogeneous than in the USA. Here 37% (96) are published in Q1, 22% (58) in Q2, 11% (29) in Q3 and 2% (6) in Q4 (Table 2). Within this group of articles, the document by Schwan[23] has 150 citations. Despite being a relatively old article, it is considered a classic as it explains the fermentation process when different microorganisms are inoculated and its influence on metabolite production.

Regarding the United Kingdom, there are 81 (44%) documents published in Q1 journals; 19 (10%) in Q2, 1% in Q3 and the same percentage in Q4 (Table 2). These publications have achieved 8177 citations. From this section, one of the most cited articles addresses the formation of volatiles from the interactions of Maillard reactions.[21]

Germany has a total of 148 scientific publications, in which nearly 53% is published in Q1 and nearly 26% in journals with no category (Table 2). One of the most cited articles (165 citations) is by Frauendorfer and Schieberle.[24] This work presents a comparative analysis of the aromas in roasted and unroasted Criollo cocoa extracts and the metabolites associated with each sensory profile.

As far as Spain is concerned, nearly 60% of the total publications are in Q1. The most cited article deals with the effect of roasting on the total dietary fiber content and the reduction in sugar content and how this affects the formation of Maillard polymers.[25]

The publications of Italy, France, China, India and Indonesia represent 15% of the total production in this topic (as shown in Table 2). Most of the documents are in Q1 ranked journals and with a significant presence in non-categorized journals as well. Among the articles published by Italy, we highlight the document by Caligiani et al.,[26] which for the first time presents the metabolic profile of cocoa beans using 1H NMR techniques on polar extracts of fermented cocoa beans from different varieties (Forastero, Criollo and Trinitario) and origins (Ecuador, Ghana, Grenada and Trinidad). A notable publication from France, recognized for its number of citations (174), is by Risterucci et al.,[27] In this study, a high-density molecular linkage map was constructed using a mapping population of 181 progenies from a cross between two heterozygous genotypes, a Forastero and a Trinitario, to explore their relationship with quality. A significant publication from China by Luna et al.,[28] details the chemical composition contributing to the flavor of cocoa liquor from a self-pollinated population of the Ecuadorian clone EET 95. One of the most cited articles from India (98 citations) examines the sensitivity to desiccation and freezing of recalcitrant cocoa seeds and its impact on quality.[29] In Indonesia, research by Jinap et al.,[30] focused on identifying specific aroma precursors of cocoa and methylpyrazines in under-fermented cocoa beans obtained from fermentation induced by endogenous carboxypeptidase. The under-fermented cocoa beans exhibited significantly higher levels of hydrophilic peptides and free hydrophobic amino acids compared to non-fermented beans. These essential cocoa aroma components may result from the breakdown of proteins and polypeptides by endogenous carboxypeptidase activated during fermentation.

Figure 3 shows the collaboration network among countries. In the figure, six major communities are identified, formed through academic collaboration between countries. The size of the node is determined by the degree, which indicates the frequency of international collaboration. The visualization of nodes and links over the time shows that the scientific community consolidated from 2015 onwards because the number of links are higher than the number of nodes, indicating more studies among the same countries. The countries with the highest levels of collaboration are the USA, Germany, the United Kingdom and France. In Figure 3 the communities are represented by different colors, with the purple community being the largest. A classic document in the purple community that includes Brazil and Portugal is by Do Carmo Brito et al.,[31] The study analyzed the fermentation and processing of cocoa over 144 hr, revealing chemical and microscopic changes. Fermentation reduced phenolic compounds and protein bodies, while drying and roasting, caused cellular damage. The main chemical changes involved reducing sugars, amino acids, proteins and phenols. From the green community a recent collaborative study between Germany and Switzerland focuses on the influence of aerobic and anaerobic incubation on the formation of non-volatile compounds, comparing them with unfermented cocoa beans and those with spontaneous fermentation.[32]

Figure 3:

Country Network Analysis.

Figure 3 also shows the communities by size. In this figure there are three main communities where collaboration between countries is more diverse. Additionally, in the graph of nodes and links over time, it can be observed that starting from 2013, there are more links than nodes, indicating an increase in the number of collaborations between countries-a trend that continues to grow.

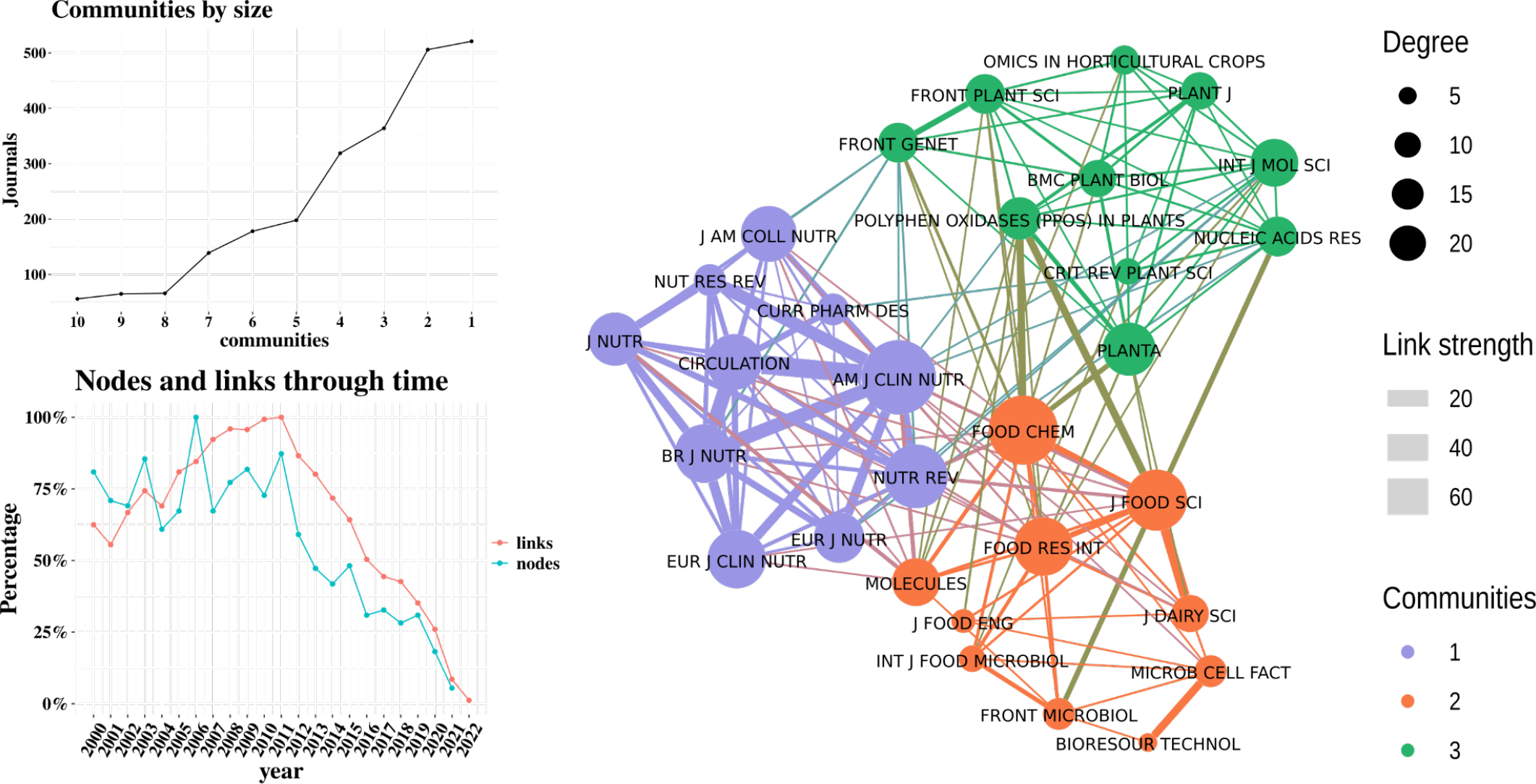

Journal analysis

In Table 3, the journals with the highest number of publications, their impact factor, H-index and quartile are reported. Food Chemistry and Food Research International have a similar number of publications, both ranked similarly in terms of quartiles. Interestingly, the top 10 journals include a conference proceedings journal without categorization, possibly because it compiles several documents from events in the studied area of knowledge. Otherwise, all the journals in this top 10 are well-established scientific journals, categorized in the highest ranking and have H-indices above 100.

| Journal | Wos | Scopus | Impact Factor | H-Index | Quantile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Chemistry | 40 | 55 | 1.75 | 324 | Q1 |

| Food Research International. | 48 | 46 | 1.5 | 212 | Q1 |

| Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. | 34 | 41 | 1.11 | 345 | Q1 |

| Journal of Food Science. | 16 | 43 | 0.78 | 179 | Q1 |

| Journal of The Science of Food and Agriculture. | 18 | 42 | 0.75 | 174 | Q1 |

| Nutrients | 15 | 34 | 1.3 | 209 | Q1 |

| Appetite | 4 | 33 | 1.27 | 178 | Q1 |

| Iop Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. | 0 | 27 | 0.2 | 48 | – |

| European Food Research and Technology. | 19 | 20 | 0.67 | 122 | Q1 |

| Lwt-Food Science and Technology. | 24 | 0 | 1.31 | 172 | Q1 |

Figure 4 shows the citation network between journals and the clustering by themes based on colors. The first cluster in green is related to metabolites and omics sciences in plantations.[33] The purple cluster relates to studies on the health effects and molecular expressions of cocoa consumption.[34] The third cluster, in orange, which is the focus of this review, relates to metabolites in the processes of transforming cocoa into chocolate. Moreover, the nodes and links visualization highlight the consolidation of journals over the time, suggesting that after 2007 the proportion of new citations has increased relative to the introduction of new journals in the field.

Figure 4:

Journal Analysis.

| No | Researcher | Total Articles* | Scopus

H-Index |

Affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pereira G | 16 | 37 | Universidade Federal Do Parana, Curitiba, Brazil. |

| 2 | Kuhnert N | 15 | 49 | Constructor University, Bremen, Germany. |

| 3 | Dewettinck K | 14 | 68 | Universiteit Gent, Ghent, Belgium. |

| 4 | Afoakwa E | 13 | 32 | Ghana Communication Technology University, Accra, Ghana. |

| 5 | De V L | 13 | 93 | Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium. |

| 6 | Biehl B | 11 | 25 | Technische Universität Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany |

| 7 | Bolini H | 11 | 46 | Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. |

| 8 | Schwan R | 11 | 56 | Universidade Federal de Lavras, Lavras, Brazil. |

| 9 | Voigt J | 11 | 25 | Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Jena, Germany. |

| 10 | D’souza R | 10 | 11 | ECA Agroindustria S.A., Concordia, Argentina. |

| 11 | Saputro A | 10 | 11 | Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. |

| 12 | Silva F | 10 | 41 | Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Porto, Portugal. |

| 13 | Van D W D | 10 | 33 | Universiteit Gent, Ghent, Belgium. |

| 14 | Andres-Lacueva C | 9 | 75 | Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. |

| 15 | Jinap S | 9 | 60 | University Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Malaysia. |

Figure 4 also shows that there are primarily three communities of journals that mostly cite each other, generating the three largest clusters. Additionally, the graph of nodes and links over time reveals that no new journals related to this research area have emerged in the last 10 years. However, the number of links has increased, indicating greater citation among existing journals.

Author collaboration network

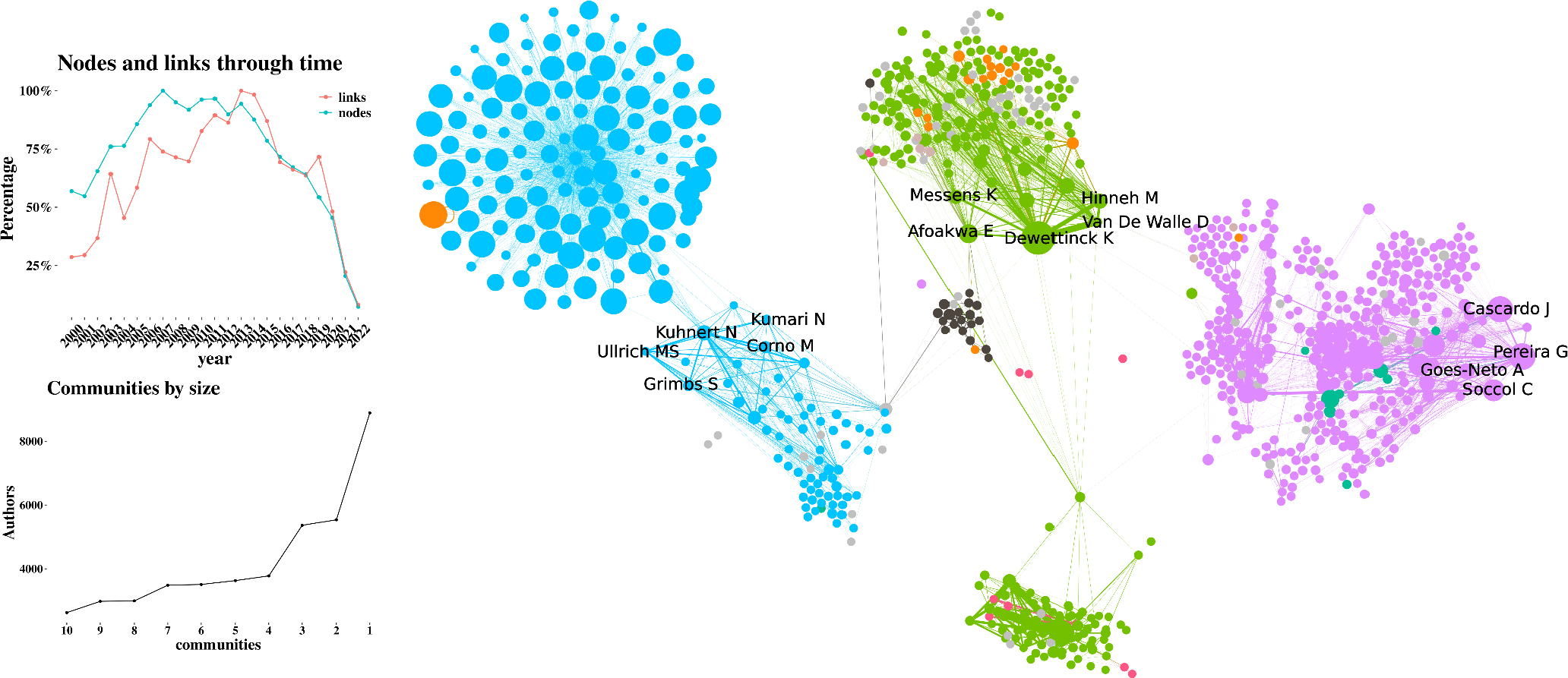

The author’s collaboration performance is approached from these perspectives: first, emphasizes the most productive authors contributing to the metabolomics or peptidomics in cacao and its influence in the chocolate quality, while the second outlines the network of academic collaborations. Table 4 Identifies Pereira, Kuhnert and Dewettinck with de major production with 16, 15 and 14 papers respectively. The most recent article with Pereira’s participation is about identifying the genes encoding enzymes in the microbiota during the fermentation of two cocoa varieties. Initial differences in the microbiota were found to unify over time due to selection pressures. The study concluded that changes in genes over time indicated specific metabolic pathways at different stages of fermentation, which can improve cocoa processing practices to ensure more stable quality in the final products.[35] On the other hand, one of the latest articles co-authored by Kuhnert involved designing an experiment using response surface methodology to model cocoa roasting and its flavor-related components. Variables included chemical compounds that change during roasting and the influence of time, temperature and the addition of water, acid and base.[36] Conversely, the most cited article in which Dewettinck has collaborated as a co-author (232 citations) is about the factors influencing the variation in the sensory profile and quality of cocoa.[2] Afoakwa and De Vuyst have participated in 13 scientific documents; Biehl, Bolini, Schwan and Voigt participated in 11 papers; D’Souza, Saputro, Silva and Van D W D in 10 papers; And Andres-Lacueva and Jinap in 9 scientific documents. Afoakwa also participated in the review published by Kongor et al.,[2] De Vuyst has been working on microorganism biodiversity and its influence on the cacao fermentation process. All these authors and their contributions will be discussed in the next section.

Figure 5 shows the three largest communities according to the number of links. These graphics aim to provide a better understanding of the authorship and citation patterns among researchers. The image depicts the ego network of the three most prolific authors. The links and nodes over time graph shows that there is a big size and density of each community, thus these authors are highly interconnected and frequently cited, corroborating their significant contributions to this field of knowledge.

Figure 5:

Author Collaboration Network.

Pereira exhibits a recurring collaboration with Schwan, with their work focusing on microbial biodiversity and its effect on cocoa transformation. Kuhnert’s community, on the other hand, has strong connections with D’Souza, Ullrich and Megias-Perez, who have deeply studied the biochemistry of the fermentation process, making significant contributions to the elucidation of peptides, sugars, polyphenols and Amadori compounds with a robust analytical platform for conducting metabolomic and peptidomic analysis. Finally, Dewettinck’s community includes collaborations with Saputro and Afoakwa, who have focused their studies on postharvest variables that can affect the sensory profile of chocolate.

Figure 5 also shows the communities formed by authors. There are three scientific communities that are more consolidated based on the number of authors they connect. Additionally, in the graph of nodes and links over time, it is evident that there is strong interaction among authors since, starting from 2011, the number of links exceeds the number of authors, indicating a strong tendency to cite works within the scientific community in this field of knowledge.

Tree of Science

Evolution of peptidomics research in cocoa

The following section shows chronologically the research dynamics in peptidomics and metabolomics of cocoa following a tree metaphor (roots, trunk and leaves). At the beginning, classical studies are presented, which are the “roots” or base of research. Then, it was compiled those that consolidate the area of knowledge the “trunk” and finally the recent research was grouped as the “leaves” approach.

Roots

The cacao protein composition has been studied since the beginning of 1900’s.[37] reported the protein fraction of the cocoa and their solubility in different solvents and polarities. Then, this fraction was characterized in 1984 and reported to contain albumins, globulins, prolamin and glutelin.[38] Moreover, it has been reported that the seeds of dicotyledonous plants primarily contain legumin-like and vicilin-like globulins.[38]

Biehl et al.,[39] later reported the effects of pH and temperature on the proteolysis process. They determined that the flavor potential increases with the decrease of pH and that these conditions may also increase proteolysis. They emphasized that proteolysis is influenced not only by pH but also by microbial activity, moisture, and acetic acid concentration within the cotyledon. Moderate levels of acetic acid (4.5-7.5 w/w) facilitate diffusion into the beans without raising acidity, while the presence of specific microorganisms can positively or negatively affect flavor depending on fermentation conditions. The authors highlighted that flavor development depends more on the specific type of peptides rather than their total quantity. They also determined optimal pH values for enzyme activity: pH 4.5 for exopeptidases and dual optima at pH 3.5 and 5.5 for endopeptidases.[39]

In the following years, Spencer and Hodge[40] deduced the amino acid sequence of cocoa albumin from cDNA, also they found that the albumin molecular weight was 21 kDa. Later, Voigt et al.,[41] reported for the first time the percentage composition of the Theobroma´s protein fraction, albumin 52% and vicilin-like globulin 43%.

The research by Voigt et al.,[42] marked the beginning of a series of studies that continued annually, each presenting new insights. In their 1994 study, they delved into the proteolytic processes occurring during fermentation. Their findings indicated that flavor precursors were derived from the digestion of vicilin, primarily catalyzed by aspartic endoprotease and carboxypeptidase. Interestingly, when the albumin fraction underwent enzymatic digestion, no specific aroma precursors were identified.[43] Expanding on this work, Voigt et al.,[42] performed the in vitro analysis of enzymatic reaction by aspartic endoprotease and carboxypeptidase. They found that the flavor precursors came from the hydrophilic oligopeptides.[42] Additionally, Bytof et al.,[44] determined that the peptides with arginine, proline, or leucine in the carboxy terminal are resistant against the degradation with carboxypeptidase, due to the enzyme preferentially liberate hydrophobic amino acid and are not able to cleave off carboxy terminal prolyl or basic amino acid residues.

The enzymatic activity during the fermentation process was further studied. Hansen et al.,[45] extracted, quantified and evaluated the enzyme activity to finally compare the performance of the different types of enzymes present during the fermentation process. They reported that the aminopeptidase, invertase and polyphenol oxidase were deactivated at the fermentation process. Moreover, carboxypeptidase was partially deactivated, whereas endoprotease and glycosidase continue active during fermentation. Finally, most of the enzymes were permanently active during the drying process, either solar or artificial drying, but polyphenol oxidase was inactivated.

Trunk

Subsequently, Hansen et al.,[46] examined enzyme activities related to flavor formation across different cocoa genotypes and maturation stages. They found lower protease activity in immature beans and reduced polyphenol oxidase activity in beans harvested four weeks before maturation. Pulp invertase activity increased with maturation and during pod storage, leading to changes in sugar composition. High-quality flavor cultivars exhibited greater protease activity but lower cotyledon invertase levels. Interestingly, despite carboxypeptidase being considered important for flavor formation, its activity was lowest in the fine flavor cultivar, suggesting no straightforward correlation between this enzyme and flavor quality. Overall, the study concluded that unfermented bean enzyme activity does not limit the formation of flavor precursors.

Hansen et al.,[46] and Jinap et al.,[47] published the results about the influence of incubation in the activation of the enzymes in dried under-fermented cocoa beans and the impact of this process in the flavor formation. Previous studies showed that most of the enzymes remain active during the drying process (excluding carboxypeptidase), but in this paper the results showed that the enzymes partially lost their activity. They implemented 4 hr of incubation of the under-fermented cocoa beans, finding that free amino acid concentration significantly increased. Likewise, the reducing sugars concentration of well-fermented beans was comparable with the under-fermented-incubated samples. The flavor quality of dried and partially fermented cocoa beans can be enhanced by activating the enzymatic machinery using an incubation process.

Building on previous scientific advances, researchers began characterizing peptides derived from vicilin to understand their sequences, origin, and transformation during the chocolate-making process. Kratzer et al.,[48] found that vicilin-like globulin consists of two major subunits (47 kDa and 31 kDa) and three smaller ones (15.5, 15.0, and 14.5 kDa), all derived from proteolytic cleavage of a 66 kDa precursor. All vicilin subunits originate from the amino acid sequence between positions 131 and 566. These subunits originate from amino acid positions 131–566, with overlapping regions and distinct proteolytic pathways. Notably, the 47 kDa and 31 kDa subunits arise independently from a common intermediate. Subsequent studies revealed that albumin also contributes to flavor precursors.[1,49] Caligiani et al.,[1] reported that Criollo genotypes, known for fine flavor, produce a higher proportion of peptides from albumin. Similarly, Marseglia et al.,[49] detected numerous albumin-derived oligopeptides in well fermented cocoa beans.

Additionally, Marseglia et al.,[49] identified and semi-quantified 44 peptides in fermented cocoa beans from different geographic regions. They found that the peptides were in the same amino acid regions reported by Kratzer et al.,[48] The preferred cleavage sites in the N-terminal were aspartic acid, asparagine and arginine suggesting the activity of the endogenous aspartic endoprotease. Even though it was reported before that the C-terminal should not have acidic amino acids due to the carboxypeptidase releasing hydrophobic amino acids. Marseglia et al.,[49] found that the preferred cleavage sites in the C-terminal were phenylalanine, glutamic acid and aspartic acid. Despite peptides with arginine, lysine, or proline residues in the C-terminal were resistant to degradation by the carboxypeptidase, Marseglia et al.,[49] found different results, as many peptides showed valine-phenylalanine sequence in their C-terminal, indicating that other proteases could be involved in the process, suggesting that may be microbial origin peptidases. When peptides were quantified, the data on roasted products exhibits that after roasting, the peptide content was reduced by approximately 30%.

Similarly, Caligiani et al.,[1] published about the peptide pattern of 48 cocoa beans samples from 22 different geographical origins and the relationship between the relative abundance of the 33 peptides identified during the fermentation time. Related to the flavor quality, they found that samples considered as fine flavor cocoa contained the highest amounts of the peptides ASKDQPL (from Ecuador), TVWRLD, IEF, DEEGNFKIL (from Malaysian and Brazil), APLSPGDVF, SPGDVF (from Ghana), GAGGGGL, RLD, VI, RRSDLD, EVL (from Mexico) and a peptide with a molecular weight of 1090 and 1596 (from Ecuador and Nigeria respectively). Moreover, they proposed that proteolytic activity depends not only on the physicochemical factors such as pH or temperature but also on the geographical origin because the region is tightly related with a specific genotype.

Up to this point in this literature review, it has been possible to identify some peptides related to complete fermentation, however, specific-cocoa aroma peptides have not yet been characterized. In this vein, Voigt et al.,[50] reported peptides associated with the formation of the cocoa-specific aroma notes through a controlled roasting process. The peptide fractions and free amino acids were roasted alongside deodorized cocoa butter and a blend of glucose and fructose. A trained test panel then assessed the resulting aroma profiles. Cocoa and malty aromas were present in the total precursor extract and the hydrophilic fraction, regardless of the presence of free amino acids. Conversely, chocolate-specific aromas were absent in the roasted hydrophobic fraction, whether free amino acids were included. Additionally, roasting the synthetic mixture of free amino acids without peptides produced bread-like, flowery and honey-like aromas, but lacked the distinctive cocoa and dark chocolate notes.

The hydrophilic peptide fraction that revealed the most cocoa-specific aroma was characterized. The most prominent sequences in this fraction were: NNPYYFPK, RNNPYYFPK. Another 52 peptides of the hydrophilic fraction were also considered to contribute to the cocoa-specific aroma, and they were identified and published in the document. They suggest that the peptides are in the amino acid positions of 140-148, 194-198, 392-398, 471-476 and 497-499 of the vicilin precursor sequences.

Later, Mayorga-Gross et al.,[51] through a non-targeted metabolomic approach studied the metabolomic differences between the three fermentation stages, 0-2, 3-4 and 5-6 days. They found that ten tentatively identified oligopeptides from 3 to 12 amino acids are discriminating against metabolites among the 37 most discriminant ions with respect to processing time. They also observed an increase in the oligopeptides to maximal levels after 3 to 4 days of fermentation and then, a drop-in intensity occurred. For this reason, they propose to revise the processing time for the transformation from beans to cocoa beans, which can be shorter than usual.

John et al.,[52] performed a controlled transformation of the cocoa beans, excluding bacterial activity, to analyze protein degradation. They simulated the fermentation matrix using ethanol and organic acids (citric, acetic, and lactic). The artificial system showed increased endoprotease activity but reduced exopeptidase activity, with vicilin-derived peptides still present after 72 hr. When compared to commercial fermentation, 60-67% of the peptides overlapped in sequence and length, though slight differences were observed at the N- and C-terminal regions. In the artificial system, the N-terminal showed a preference for aspartate, followed by valine, serine, and alanine, while in commercial fermentation, alanine and aspartate were predominant. In both cases, phenylalanine and tyrosine were favored at the C-terminal, supporting their inhibitory effect on carboxypeptidase. The study also suggested that albumin may contribute to flavor formation, as a diverse range of albumin-derived peptides, though smaller than those from vicilin, was observed. Additionally, free amino acids may also play a role in cocoa flavor development.

Regarding the peptides found after 48 hr of artificial transformation, they presented some peptides reported before in a commercial fermentation, RNNPYYFPK, NNQRIF, DEEGNFKI, NGKGTITF, QVKAPLSPGDVF and ASKDQPLN. Also, they found two peptides that were present in all the samples: APLSPGDVF and SPGDVF. In summary, they found that the proteolytic process in an artificial system simulates commercial fermentation.[52]

Leaves

In the next contribution to the elucidation of peptide identity, the authors used different times of fermentation to observe the sequential proteolytic degradation and report the largest collection of cocoa peptides at the time. Not only from vicilin and albumin, but also from lipoxygenase, peroxidase and chitinase. D’Souza et al.,[6] identified 392 peptides from vicilin, 167 from albumin, 26 from peroxidase and 20 from lipoxygenase, 20 from chitinase and 241 smaller peptides from multiple proteins. They also reported a general pattern that the fermentation time is inversely proportional to the length of the peptide. As time progressed, the peptides identified were smaller and no peptides were detected in fresh unfermented beans. The length of the peptides at 24 hr of fermentation were between 21 to 23 amino acids, from 48 to 72 hr between 7 to 20 amino acids and from 72 to 96 hr between 3 to 6 amino acids. After 96 hr there was a high increase in di, tri, tetra and pentapeptides. They also highlight that two-thirds of all peptides detected have lengths from 2 to 5 amino acids.

Regarding the flavor formation, N-terminal and C-terminal amino acids, ti was found that methionine, leucine, valine, isoleucine, phenylalanine and alanine in the N-terminal tend to react with reducing sugars producing carboxylic acids, Strecker amines and aldehydes; that produces characteristic cocoa aroma. On the other hand, the bitter tasting could be formed by the intramolecular cyclization at the N-terminal producing diketopiperazines. Furthermore, Tyrosine residues are the most abundant at the C-terminal. Gly and Gln residues at the C-terminal also showed a high relative abundance. Thr and Val residues at the C-terminal tend to be short-lived. Finally, they argue that hundreds of more reactive and more abundant smaller peptides might be cocoa flavor precursors and certainly plays the largest role in flavor formation.[6]

Interestingly, recent research is focused on investigating from this complex and large peptidome, those specific peptides associated with the development of cocoa flavor. In other words, peptides can be considered as flavor precursors metabolites, because they are linked to the development of a specific quality sensory attribute in chocolate.

In this way, Scollo et al.,[53] characterized the peptide and protein profiles of IMC 67 genotypes of cacao at different fermentation stages. In this study, 1,058 endogenous peptides were identified and quantified, making these results the largest collection of cocoa peptides up to now. Also, they propose potential biomarkers of the fermentation process. The results showed that 315 peptides were found on day 0, 710 peptides during day 2, 626 during day 4 and 286 peptides during day 6. The ontology of those peptides was as follows: 502 peptides from vicilin, 144 peptides from 21kDa albumin, 60 from lipoxygenase, 40 from RmLC cupin, 29 from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and 28 from peroxygenase, among others. To identify the potential biomarkers three statistical filters were applied. First, the highest abundance among the fourth fermentation day. Second, a fold change greater than 4 between the highest and lowest intensities. Third, the absence on day 0. Consequently, they found 192 differential peptides on day 2, 46 at day 4 and 21 at day 6.

Then, Escobar et al.,[7] explained that fine cocoa attributes were found at 96 hr of fermentation and the peptide precursors present in higher intensities in the fermented beans at this time of process were FGVPSK (from vicilin amino acid region 519-524), NHR, LPSVK, LLC, LKY, VDNIFNNPDESY (vicilin 526-537). They also reported that the peptide AGGGGL (from albumin amino acid region 54-59) was found at a lower intensity at 96 hr of fermentation. Moreover, this study presented other differential peptides considered as candidate biomarkers of quality at 72, 120 and 144 hr of fermentation, which are associated with high, medium, or low sensory quality.

Evolution of targeted and untargeted metabolomics research on carbohydrates

Roots

Despite the relevance of carbohydrates and their biochemical changes during the transformation of cocoa seeds to beans and to chocolate, these were initially under-studied. The research was mostly focused on the study of peptides. Nevertheless, the first studies include the identification of sugars in roasted cocoa beans or nibs.[54] These studies observed that nibs contained mainly D-fructose, D-glucose, sucrose and raffinose oligosaccharides. Other carbohydrates such as stachyose, melibiose, manninotriose, planteose, verbascose, verbascotetraose and mesoinositol were also detected.

In 1966 the quantification of total sugars (0.34 to 1.38%) and reducing sugars (0.39 to 3.48%) in nibs from were reported by Rohan and Stewart.[55] Afterwards, new research Rohan and Stewart[56] also revealed the dynamics of reducing sugars in African cocoa seeds during fermentation in heaps. The authors found the maximum concentration at 2 or 3 days of the transformation process. Subsequently, the concentration of reducing sugars stayed relatively constant before decreasing marginally towards the end of fermentation. They also observed an almost complete degradation of reducing sugars and a substantial reduction in total sugars during roasting.

Reineccius et al.,[57] highlighted the importance of carbohydrates in the cocoa metabolomic fingerprint due to their role in flavor formation. During spontaneous fermentation, sucrose is converted into reducing sugars like fructose and glucose, which act as key flavor precursors during roasting via Maillard reactions. These sugars react with amino acids and peptides to generate aroma-active compounds such as pyrazines, furans, furanones, esters, aldehydes, ketones, pyrroles, aldols, and terpenes, all contributing to chocolate’s final flavor. The authors were the first to quantify individual sugars in fermented and dried beans from various geographic origins, consistently identifying fructose, sorbose, glucose, sucrose, inositol, mannitol, and pentitol. Variations in sugar concentrations were linked to harvest and postharvest practices, with highly fermented beans showing lower sucrose and 2–16 times more fructose than glucose.

Trunk

The research was focused on studying the dynamics of sugars during the transformation of seeds to cocoa beans. Hashim et al.,[58] revealed that during fermentation, the sucrose and total sugars decreased significantly in 89 and 75%, respectively. This implied the increase of total reducing sugars. Thus, fructose, glucose, mannitol, inositol and total reducing sugars concentrations peaked after 4 days of fermentation, then gradually decreased until the process concluded.

The research was also focused on the study of enzymes that act on sugars. In this sense, as the endogenous enzymatic activity of invertase has only briefly been studied, new research was done with the aim to characterize the activity of this enzyme in the cotyledon during cocoa fermentation.[59] This enzyme plays a crucial role in reducing sugars. It was reported that the overall cotyledon invertase activity was low, with invertase activity nearly disappearing within 2 days of fermentation. Although sugar inversion persisted for 5 days, only minimal levels of cotyledon invertase activity were detectable after the first 2 days of fermentation.

Subsequent studies[60,61] examined changes in fructose, glucose, mannitol, and sucrose during spontaneous fermentation, particularly under the influence of starter culture inoculation. Sucrose levels declined steadily after 24 hr, while glucose and fructose increased. Mannitol appeared after 12 hr and stabilized after 60 hr. Monitoring sugar concentration dynamics helps identify peak metabolite production within the cocoa seed, revealing clear phases of accumulation and decline. This information is valuable for defining optimal fermentation times, which are often predetermined without considering the concentration of flavor precursors. Therefore, processing should be planned based on metabolite profiles to improve both flavor quality and process efficiency.

Afterwards, a new study[62] carried out the transformation of cocoa seeds under controlled conditions in comparison with spontaneous fermentation to analyze if flavor precursors, such as reducing sugars, were produced in similar quantities in both processes. In this study, the process was performed by controlling the temperature, the acidification was conducted using acetic and lactic acids and the absence of microorganisms. The concentration of reducing sugars found in the treatments of controlled conditions (16.4-28.0 mg g-1 ffdm) was higher than the reported spontaneous fermentation (3.3 and 11.1 mg g-1 ffdm). For this reason and considering that sugars are limiting compounds in reactions of chocolate flavor formation, the treatment under controlled conditions appears as an alternative way of cocoa transformation method with high potential to manage the cocoa flavor, as it allows to obtain a higher quantity of the limiting compounds of flavor-forming reactions.

Subsequently, the research of Mayorga-Gross et al.,[51] combined the untargeted metabolomic analysis with multivariate statistics and the main results to be highlighted were that sugars (such as sucrose) are one of the most discriminating chemical groups in spontaneous cocoa fermentation. It means that sugars discriminate between the fermentation time causing the formation of clusters according to the days of the process.

New research assessed the effect of Pod Storage (PS) (0, 3 and 7 days of PS) on specific flavor precursor development focused on reducing sugars and free amino acid profiles and the implications in the volatile aroma compounds formation in the cocoa liquor.[63] The authors found that PS contributes to a slight increase in the total content of reducing sugars in cocoa beans. Also, they suggest that 7 days of PS seemed to improve the formation volatiles. Hinneh et al.,[63] stated that these findings could be considered to improve the flavor potential of cocoa beans considering that both, reducing sugars and amino acids/peptides, are the flavor precursors that generate aromas that may produce a fine or a basic flavor profile.

Leaves

Subsequently, pioneering studies were developed with the aim to find relationships between the sugars as flavor precursors with the volatile and sensory profiles of derived chocolate.[64,65] Hinneh et al.,[64] observed that an increase in the overall volatile concentration when long PS (7 days of PS) were applied, could be attributed to the onset of widespread degradation of the cocoa pulp, making available reducing sugars. In all cases, regardless of the cacao origin/variety (categorized as fine or bulk), chocolates processed under moderate-high roasting temperatures (135-160ºC) and After 7 days, pyrazines (cocoa/nutty/roasted aromas), acids (sour perception), esters (fruity/floral/sweet aromas), furans (roasted/cheesy/green aromas), pyrroles (caramel aroma) and undesirable volatiles such as dimethyldisulfide (sulfurous) and 2-methoxyphenol (smoky) were perceived.

In this sense, according to these previous findings, Hinneh et al.,[64,65] suggest that it is possible to boost the aromatic quality of bulk cocoa in the function of the targeted aroma profile, considering the optimization of the conditions/variables of postharvesting transformation operations from seeds to beans and/or through the processing processes of the cocoa beans into chocolate.

Recent studies[66,67] used untargeted approaches to analyze Low Molecular Weight Carbohydrates (LMWCs) in unfermented and fermented cocoa beans from different origins and fermentation methods (spontaneous and starter culture-based). For the first time, iminosugars were identified. Quantitative analysis showed sucrose as the dominant carbohydrate in unfermented beans, averaging 1,165.7 mg/100 g (range: 230-4,086.8 mg/100 g), followed by raffinose (399.7 mg/100 g) and stachyose (211.4 mg/100 g). These sugars were generally reduced after fermentation. Glucose content varied across processing types, with unfermented beans averaging 74.5 mg/100 g, spontaneously fermented beans 28.3 mg/100 g, and starter culture-fermented beans 48.1 mg/100 g. In contrast, fructose levels remained relatively consistent regardless of fermentation status.[66]

Moreover, in this study, the authors proposed that stachyose, raffinose, sucrose, hexosyl glycerol, melibiose and three unknown disaccharides were candidate markers of the cocoa beans’ transformation.

Soon after, Megías-Pérez et al.,[67] corroborated the presence of sucrose and melibiose, raffinose, stachyose, fructose, glucose and galactose, maltose isomers E and Z, galactinol (O-α-D-galactopyranosyl-(1→3)-D- myo-inositol).

In unfermented cocoa, myo-inositol, scylloinositol, 1-kestose and 6-kestose were identified, along with minor LMWC tentatively identified as fructosyl-glucoses, diglycosyl-glycerol and glucosyl-sucrose. This study assessed new potential marker candidates for cocoa bean origin or fermentation status, focusing on scylloinositol, 1-kestose and galactinol. Significant differences in scylloinositol content were found among different origins, regardless of fermentation status. Additionally, galactinol was suggested as a potential indicator of fermentation status due to its absence in fermented beans.[67]

Recent comprehensive research by Megias-Perez et al.,[68] provided a thorough characterization and quantification of LMWC, detailing their changes during spontaneous fermentation and elucidating unprecedented mechanistic insights into their chemical/enzymatic degradation reactions. They observed a decrease in di- and oligosaccharides (except melibiose) with an average content loss of 95% for sucrose, 94% for raffinose, 90% for 1-kestose and 81% for stachyose, compared to unfermented seeds. Conversely, increases were noted in mannitol, 69% for fructose and 97% for glucose. Myo-inositol and scylloinositol contents also decreased by 4% and 22%, respectively, while galactinol content diminished until it vanished between 48 and 96 hr of fermentation.

Furthermore, they identified the period between 48 and 96 h as critical for significant changes in the LMWC profile. These findings align with previous studies on concurrent biochemical reactions, such as proteolysis, which similarly pinpoint critical times for generating flavor precursors like peptides and free amino acids.[51,69]

Finally, the authors tentatively proposed the kinetics of LMWC degradation (excluding monosaccharides), noting that sucrose, raffinose and stachyose best fit a first-order kinetic model, suggesting their degradation via acidic hydrolysis or enzymatic hydrolysis under acidic conditions. For raffinose and 1-kestose, a zero-order kinetic model was more fitting, indicating enzymatic hydrolysis mechanisms under acidic conditions.

CONCLUSION

Peptidomics, along with targeted and untargeted metabolomics, have contributed to comprehending the dynamics of cocoa flavor precursor metabolites’ formation, namely peptides and sugars. On one hand, these provide insights into their behavior over processing time, particularly during transformation from seeds to beans. This is crucial as it reveals points of heightened intensity for these metabolites during process time, where obtaining superior quality attributes is more probable and the process could be faster, for instance, by employing a shorter fermentation time.

On the other hand, these approaches facilitate the establishment of biomarkers associated with sensory quality attributes. Also, these metabolites can be utilized to differentiate the cacao origin and the processing time. In the case of peptides, these include fine flavor cocoa biomarkers such as ASKDQPL, TVWRLD, IEF, DEEGNFKIL, APLSPGDVF, SPGDVF, GAGGGGL, RLD, VI, RRSDLD, EVL, FGVPSK, NHR, LPSVK, LLC, LKY, VDNIFNNPDESY. And the cocoa-specific aroma biomarkers such as NNPYYFPK, RNNPYYFPK. As for sugars, sucrose and galactinol as discriminating metabolites of the fermentation time and scylloinositol of the cocoa origin.

Moreover, cocoa seeds have other carbohydrate types that have been identified by advanced instrumental techniques. However, their contribution to flavor formation has been little studied. Further research is required about the influence of postharvest transformation and agro-industrial processing stages on: 1. The biochemical transformation of the diversity of cocoa carbohydrates, 2. The chemical and/or enzymatic mechanisms linked to their degradation, 3. The interaction with other compounds in the cocoa seeds and 4. The participation in optimum quantity terms in non-enzymatic browning reactions that produce volatile organic flavor compounds, which define the quality in the sensory profile.

Despite the genetic origin and agroclimatic conditions influences quality, we found that to generate high-quality flavor cocoa, it is essential to work intensively on postharvest processes and practices. Future research should focus on analyzing the optimal conditions of the postharvest transformation operations to produce fine flavor metabolites responsible for high-quality cocoa attributes. This could consider the generation of specific metabolites related to fine quality (high quality biomarkers related to peptides and carbohydrates), the optimal flavor precursors concentration, the optimal conditions that promote the enzyme activities involved for the generation of this type of metabolites, as well as the other non-enzymatic reactions (i.e., acidic hydrolysis, oxidation), which contribute the production of cocoa with specialty flavor characteristics.

Finally, this review provides both practical and theoretical contributions to the field of cocoa research. Practically, by identifying key flavor-related metabolites such as specific peptides and carbohydrates, it offers valuable insights for optimizing postharvest processing practices aimed at enhancing cocoa flavor quality. The identification of potential quality biomarkers opens new opportunities for monitoring and controlling fermentation and drying processes to produce specialty cocoa with consistent sensory profiles. Furthermore, the findings offer guidance for the development of differentiated chocolate products targeted at premium markets.

From a theoretical perspective, this review consolidates and organizes existing knowledge on cocoa metabolomics and peptidomics, applying for the first time the “Tree of Science” methodology to map the evolution and structure of this scientific domain. This approach reveals critical knowledge gaps, such as the need for further studies on carbohydrate transformation mechanisms and metabolite interactions during processing. Additionally, the scientometric analysis provides a novel framework for understanding research trends and offers a foundation for proposing new hypotheses related to the biochemical pathways influencing cocoa flavor. Overall, this study contributes significantly to advancing both applied and fundamental knowledge in cocoa science.

Cite this article:

Zuluaga M, Santander M, Escobar S, Vaillant F. Metabolomics and Peptidomics in Cocoa: Scientometrics Analysis and Systematic Review of Flavor-Related Chemical Compounds in Postharvest Transformation. J Scientometric Res. 2025;14(3):x-x.

References

- Caligiani A, Marseglia A, Prandi B, Palla G, Sforza S.. Influence of fermentation level and geographical origin on cocoa bean oligopeptide pattern.. Food Chem.. 2016;211:431-9. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Kongor JE, Hinneh M, De Walle DV, Afoakwa EO, Boeckx P, Dewettinck K., et al. Factors influencing quality variation in cocoa () bean flavour profile – a review.. Food Res Int.. 2016;82:44-52. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ríos F, Ruiz A, Lecaro J, Rehpani C.. Array. Bogotá D.. 2017:140 C.: Fundación Swisscontact Colombia [cited Jun 19 2024]. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Santander Muñoz M, Rodríguez Cortina J, Vaillant FE, Escobar Parra S.. An overview of the physical and biochemical transformation of cocoa seeds to beans and to chocolate: flavor formation.. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.. 2020;60(10):1593-613. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Aprotosoaie AC, Luca SV, Miron A.. Flavor chemistry of cocoa and cocoa products-an overview.. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf.. 2016;15(1):73-91. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza RN, Grimbs A, Grimbs S, Behrends B, Corno M, Ullrich MS, et al. Degradation of cocoa proteins into oligopeptides during spontaneous fermentation of cocoa beans.. Food Res Int.. 2018;109:506-16. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Escobar S, Santander M, Zuluaga M, Chacón I, Rodríguez J, Vaillant F., et al. Fine cocoa beans production: tracking aroma precursors through a comprehensive analysis of flavor attributes formation.. Food Chem.. 2021;365:130627 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Barišić V, Kopjar M, Jozinović A, Flanjak I, Ačkar Đ, Miličević B, et al. The chemistry behind chocolate production.. Molecules.. 2019;24(17):3163 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Saltini R, Akkerman R, Frosch S.. Optimizing chocolate production through traceability: a review of the influence of farming practices on cocoa bean quality.. Food Control.. 2013;29(1):167-87. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Robledo S, Zuluaga M, Valencia-Hernandez LA, Arbelaez-Echeverri OA, Duque P, Alzate-Cardona JD., et al. Tree of science with Scopus: a shiny application.. ISTL.. 2022(100) [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Zuluaga M, Robledo S, Arbelaez-Echeverri O, Osorio-Zuluaga GA, Duque-Méndez N.. Tree of science – tos: a web-based tool for scientific literature recommendation.. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship. 2022(100) [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions.. version 6.3; updated Feb 2022. Cochrane. :2022 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M.. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks.. ICWSM.. 2009;3(1):361-2. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Stark T, Hofmann T.. Structures, sensory activity and dose/response functions of 2,5-diketopiperazines in roasted cocoa nibs().. J Agric Food Chem.. 2005;53(18):7222-31. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Camu N, De Winter T, Addo SK, Takrama JS, Bernaert H, De Vuyst L., et al. Fermentation of cocoa beans: influence of microbial activities and polyphenol concentrations on the flavour of chocolate.. J Sci Food Agric.. 2008;88(13):2288-97. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ho VT, Zhao J, Fleet G.. The effect of lactic acid bacteria on cocoa bean fermentation.. Int J Food Microbiol.. 2015;205:54-67. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Batista NN, Ramos CL, Ribeiro DD, Pinheiro AC, Schwan RF.. Dynamic behavior of and Hanseniaspora uvarum during spontaneous and inoculated cocoa fermentations and their effect on sensory characteristics of chocolate.. LWT Food Sci Technol.. 2015;63(1):221-7. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ho VT, Zhao J, Fleet G.. Yeasts are essential for cocoa bean fermentation.. Int J Food Microbiol.. 2014;174:72-87. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Raksakulthai R, Haard NF.. Exopeptidases and their application to reduce bitterness in food: a review.. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.. 2003;43(4):401-45. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Becerra LD, Zuluaga M, Mayorga EY, Moreno FL, Ruíz RY, Escobar S., et al. Cocoa seed transformation under controlled process conditions: modelling of the mass transfer of organic acids and reducing sugar formation analysis.. Food Bioprod Process.. 2022;136:211-25. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio D, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Spencer JP, Tognolini M, Borges G, Crozier A., et al. Dietary (Poly)phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases.. Antioxid Redox Signal.. 2013;18(14):1818-92. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Lonchampt P, Hartel RW.. Fat bloom in chocolate and compound coatings.. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol.. 2004;106(4):241-74. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Schwan RF.. Cocoa fermentations conducted with a defined microbial cocktail inoculum. Appl Environ Microbiol.. 1998;64(4):1477-83. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Frauendorfer F, Schieberle P.. Changes in key aroma compounds of criollo cocoa beans during roasting.. J Agric Food Chem.. 2008;56(21):10244-51. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Esteban RM, Mollá E, López-Andréu FJ.. Roasting effects on dietary fiber composition of cocoa beans.. J Food Sci.. 1994;59(1):123-4. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Caligiani A, Acquotti D, Cirlini M, Palla G.. 1H NMR Study of Fermented Cocoa ( L.) beans.. J Agric Food Chem.. 2010;58(23):12105-11. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Risterucci AM, Grivet L, N’Goran JA, Pieretti I, Flament MH, Lanaud C., et al. A high-density linkage map of Theobroma cacao L. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2000;101(5):948-55. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Luna F, Crouzillat D, Cirou L, Bucheli P.. Chemical composition and flavor of Ecuadorian cocoa liquor.. J Agric Food Chem.. 2002;50(12):3527-32. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Chandel KP, Chaudhury R, Radhamani J, Malik SK.. Desiccation and freezing sensitivity in recalcitrant seeds of tea, cocoa and jackfruit.. Ann Bot.. 1995;76(5):443-50. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Jinap S, Ikrawan Y, Bakar J, Saari N, Lioe HN.. Aroma precursors and methylpyrazines in underfermented cocoa beans induced by endogenous carboxypeptidase.. J Food Sci.. 2008;73(7):H141-7. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Do Carmo Brito BN, Campos Chisté R, Da Silva Pena R, Abreu Gloria MB, Santos Lopes A.. Bioactive amines and phenolic compounds in cocoa beans are affected by fermentation.. Food Chem.. 2017;228:484-90. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter A, Hühn T, Kneubühl M, Chatelain K, Rohn S, Chetschik I., et al. Comparison of the aroma composition and sensory properties of dark chocolates made with moist incubated and fermented cocoa beans.. J Agric Food Chem.. 2022;70(13):4057-65. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Araújo DM, De Almeida AF, Pirovani CP, Mora-Ocampo IY, Lima Silva JP, Valle Meléndez RR., et al. Molecular, biochemical and micromorphological responses of cacao seedlings of the Parinari series, carrying the lethal gene Luteus-Pa, in the presence and absence of cotyledons.. Plant Physiol Biochem.. 2023;194:550-69. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Grassi D, Necozione S, Lippi C, Croce G, Valeri L, Pasqualetti P, et al. Cocoa reduces blood pressure and insulin resistance and improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypertensives.. Hypertension.. 2005;46(2):398-405. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Lima CO, De Castro GM, Solar R, Vaz AB, Lobo F, Pereira G, et al. Unraveling potential enzymes and their functional role in fine cocoa beans fermentation using temporal shotgun metagenomics.. Front Microbiol.. 2022;13:994524 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Andruszkiewicz PJ, D’Souza RN, Corno M, Kuhnert N.. Novel Amadori and Heyns compounds derived from short peptides found in dried cocoa beans.. Food Res Int.. 2020;133:109164 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- The vegetable proteins.. Nature.. 1924;114(2875):822 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Higgins TJ.. Synthesis and regulation of major proteins in seeds.. Annu Rev Plant Physiol.. 1984;35(1):191-221. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Biehl B, Brunner E, Passern D, Quesnel VC, Adomako D.. Acidification, proteolysis and flavour potential in fermenting cocoa beans.. J Sci Food Agric.. 1985;36(7):583-98. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Spencer ME, Hodge R.. Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding the major albumin of : identification of the protein as a member of the Kunitz protease inhibitor family.. Planta.. 1991;183(4):528-35. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Voigt J, Biehl B, Wazir SK.. The major seed proteins of L. food Chemistry.. 1993;47(2):145-51. [cited Jun 19 2024] [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Voigt J, Biehl B, Heinrichs H, Kamaruddin S, Marsoner GG, Hugi A., et al. Array. Food Chem.. 1994;49(2):173-80. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Voigt J, Heinrichs H, Voigt G, Biehl B.. Cocoa-specific aroma precursors are generated by proteolytic digestion of the vicilin-like globulin of cocoa seeds.. Food Chem.. 1994;50(2):177-84. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Bytof G, Biehl B, Heinrichs H, Voigt J.. Specificity and stability of the carboxypeptidase activity in ripe, ungerminated seeds of L. food Chemistry. 1995;54(1):15-21. [cited Jun 19 2024]. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JE, Sato M, Lacis A, Ruedy R, Tegen I, Matthews E., et al. Climate forcings in the Industrial era.. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.. 1998;95(22):12753-8. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hansen CE, Mañez A, Burri C, Bousbaine A.. Comparison of enzyme activities involved in flavour precursor formation in unfermented beans of different cocoa genotypes.. J Sci Food Agric.. 2000;80(8):1193-8. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Jinap MS, Nazamid S, Jamilah B.. Activation of remaining key enzymes in dried under-fermented cocoa beans and its effect on aroma precursor formation.. Food Chem.. 2002;78(4):407-17. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer U, Frank R, Kalbacher H, Biehl B, Wöstemeyer J, Voigt J., et al. Subunit structure of the vicilin-like globular storage protein of cocoa seeds and the origin of cocoa- and chocolate-specific aroma precursors.. Food Chem.. 2009;113(4):903-13. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Marseglia A, Sforza S, Faccini A, Bencivenni M, Palla G, Caligiani A., et al. Extraction, identification and semi-quantification of oligopeptides in cocoa beans.. Food Res Int.. 2014;63:382-9. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Voigt J, Janek K, Textoris-Taube K, Niewienda A, Wöstemeyer J.. Partial purification and characterisation of the peptide precursors of the cocoa-specific aroma components.. Food Chem.. 2016;192:706-13. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Mayorga-Gross AL, Quirós-Guerrero LM, Fourny G, Vaillant F.. An untargeted metabolomic assessment of cocoa beans during fermentation.. Food Res Int.. 2016;89:901-9. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- John WA, Kumari N, Böttcher NL, Koffi KJ, Grimbs S, Vrancken G, et al. Aseptic artificial fermentation of cocoa beans can be fashioned to replicate the peptide profile of commercial cocoa bean fermentations.. Food Res Int.. 2016;89(1):764-72. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Scollo E, Neville DC, Oruna-Concha MJ, Trotin M, Umaharan P, Sukha D, et al. Proteomic and peptidomic UHPLC-ESI MS/MS analysis of cocoa beans fermented using the Styrofoam-box method.. Food Chem.. 2020;316:126350 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Cerbulis J.. Carbohydrates in cacao beans. II. Sugars in Caracas cacao beans. Arch Biochem Biophys.. 1955;58(2):406-13. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Rohan TA, Stewart T.. The precursors of chocolate aroma: changes in the sugars during the roasting of cocoa beans.. J Food Sci.. 1966;31(2):206-9. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Rohan TA, Stewart T.. The precursors of chocolate aroma: production of reducing sugars during fermentation of cocoa beans.. J Food Sci.. 1967;32(4):399-402. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Reineccius GA, Andersen DA, Kavanagh TE, Keeney PG.. Identification and quantification of the free sugars in cocoa beans.. J Agric Food Chem.. 1972;20(2):199-202. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hashim P, Selamat J, Syed Muhammad SK, Ali A.. Changes in free amino acid, peptide-N, sugar and pyrazine concentration during cocoa fermentation.. J Sci Food Agric.. 1998;78(4):535-42. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hansen CE, Olmo MD, Burri C.. Enzyme activities in cocoa beans during fermentation.. J Sci Food Agric.. 1998;77(2):273-81. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Crafack M, Mikkelsen MB, Saerens S, Knudsen M, Blennow A, Lowor S, et al. Influencing cocoa flavour using and in a defined mixed starter culture for cocoa fermentation.. Int J Food Microbiol.. 2013;167(1):103-16. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Lefeber T, Gobert W, Vrancken G, Camu N, De Vuyst L.. Dynamics and species diversity of communities of lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria during spontaneous cocoa bean fermentation in vessels.. Food Microbiol.. 2011;28(3):457-64. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Kadow D, Niemenak N, Rohn S, Lieberei R.. Fermentation-like incubation of cocoa seeds ( L.) – Reconstruction and guidance of the fermentation process.. LWT Food Sci Technol.. 2015;62(1):357-61. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hinneh M, Semanhyia E, Van De Walle D, De Winne A, Tzompa-Sosa DA, Scalone GL, et al. Assessing the influence of pod storage on sugar and free amino acid profiles and the implications on some Maillard reaction related flavor volatiles in Forastero cocoa beans.. Food Res Int.. 2018;111:607-20. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hinneh M, Van De Walle D, Tzompa-Sosa DA, Haeck J, Abotsi EE, De Winne A, et al. Comparing flavor profiles of dark chocolates refined with melanger and conched with Stephan mixer in various alternative chocolate production techniques.. Eur Food Res Technol.. 2019;245(4):837-52. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hinneh M, Abotsi EE, Van De Walle D, Tzompa-Sosa DA, De Winne A, Simonis J, et al. Pod storage with roasting: A tool to diversifying the flavor profiles of dark chocolates produced from ‘bulk’ cocoa beans? (Part II: Quality and sensory profiling of chocolates).. Food Res Int.. 2020;132:109116 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Megías-Pérez R, Grimbs S, D’Souza RN, Bernaert H, Kuhnert N.. Profiling, quantification and classification of cocoa beans based on chemometric analysis of carbohydrates using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry.. Food Chem.. 2018;258:284-94. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Megías-Pérez R, Ruiz-Matute AI, Corno M, Kuhnert N.. Analysis of minor low molecular weight carbohydrates in cocoa beans by chromatographic techniques coupled to mass spectrometry.. J Chromatogr A.. 2019;1584:135-43. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Megias-Perez R, Moreno-Zambrano M, Behrends B, Corno M, Kuhnert N.. Monitoring the changes in low molecular weight carbohydrates in cocoa beans during spontaneous fermentation: A chemometric and kinetic approach.. Food Res Int.. 2020;128:108865 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Kumari N, Kofi KJ, Grimbs S, D’Souza RN, Kuhnert N, Vrancken G, et al. Biochemical fate of vicilin storage protein during fermentation and drying of cocoa beans.. Food Res Int.. 2016;90:53-65. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]