Contents

ABSTRACT

Framing effect is a cognitive bias that leads people to display a preference for one option between alternatives that are factually equivalent but differ in the way they are presented. The effect was demonstrated by Tversky and Kahneman following the development of Prospect Theory, gained momentum in the early 1980s, and continues to be a widely researched topic. Employing a bibliometric co-citation analysis, the current paper maps the intellectual structure of research in framing effects of the last 20 years of publications. The results reveal four clusters that represent the main areas of concentration of scholarly research on framing, providing an interesting case of the scientific development process. The first cluster reveals that framing research, although initially based on Prospect Theory, which confronted traditional expected utility theory in the field of economics, was mainly advanced in the field of psychology. Initially applied to choices between risky-choices, scholars expanded framing research to contexts where no risk is at stake, and other theories and cognitive, emotional, and motivational mechanisms were proposed. The second and third clusters revealed that framing research has been mainly applied in the fields of communication / political sciences and health, respectively. The final cluster, composed of seminal papers on framing, reveals that the framing effect remains relevant and still requires additional studies to better assess its effects on different profiles of individuals, scenarios, contexts, and methodological approaches.

INTRODUCTION

The framing effect is a cognitive bias that leads people to display a preference for one option between alternatives that are factually equivalent but differ in the way they are presented. In other words, framing effects occur when different ways of describing the same choice problem lead to different responses.[1–3] A prototypical example is depicting a glass of water as half full or half empty. Both cases represent exactly the same information: a vessel in which the water level is at the mid-point of its height. However, because the way information is presented differs, equivalent information can be more or less attractive or salient depending on what features are highlighted.

Framing effects is one of the most widely discussed deviations from rational, value-maximizing solutions in behavioral decisions,[4] and was initially demonstrated by Tversky & Kahneman[5] based on prospect theory that they had developed two years before.[6] One of the basic tenets of prospect theory is that people are more likely to take risks when experiencing a loss than when experiencing a gain, a phenomenon that became known as ‘loss aversion’. Drawing from this principle, Tversky & Kahneman[5] showed that subjects preferred sure to risky options when they were framed positively or as gains, but risky options when they were depicted negatively or as losses, even though both alternatives were equivalent. Thus, framing equivalent alternatives in terms of gains or losses causes decision-makers to miscalculate risk, and violate the axioms of dominance and invariance of expected utility theory, leading to sub-optimal decisions and choices.[4]

In the ensuing years, because of its potential applicability to many fields, framing effects were studied by scholars of a variety of disciplines. For instance, by the end of the last century, Kühberger’s meta-analysis[7] had identified 248 papers on framing effects in risky-choice decisions, and Levin et al.,’s[1] systematic literature review discussed more than ninety studies. These studies spanned very diverse research areas, from psychology and health sciences to management and communications. Since then, framing effect continues to be a topic of interest to scholars of many disciplinary domains, such as communication,[8,9] public policy,[10,11] health,[12] corporate social responsibility,[13] and consumer behavior.[14,15]

Given the wide application of the framing effect in different areas and its evolution over time, we believe the time is ripe to examine how decision frame theory has evolved more recently, in which areas it has been applied, and which scholars and publications have influenced scholarly research in the last two decades. Thus, the current research proposes to map the intellectual structure, application, and temporal evolution of the framing effect, by performing a bibliometric analysis of the last twenty years. By doing so, we aim to answer the following research questions: (i) what is the intellectual structure of the literature on framing effects? (ii) who are the central, peripheral, or bridging researchers in this field? (iii) how has the intellectual structure of the field developed over time? To answer these questions, we performed a co-citation analysis on the most important manuscripts on framing effects in the period from 2001 to 2020, connecting authors, articles, and journals through analysis of paired references.[16] We divided this period into two equal and smaller periods (2001-2010 and 2011-2020) to examine whether the intellectual structure of framing effects has changed over time.

Three common clusters were identified in both periods analyzed. The first comprises articles that build-up the understanding of the theory on the framing effect, exploring and defining the concept in situations of judgment and decision-making. The second comprises articles that analyze the framing effect in the domain of communication, involving applications and discussions regarding the role media plays in shaping public opinion. The third factor encompasses articles that examine the relative persuasion of gain- vs. loss-framed appeals on individuals’ engagement in health interventions. In addition, we identified a fourth factor, which emerged only in the second period of analysis, consisting of the seminal articles by Tversky and Kahneman,[5,17–20] suggesting a resurgence of interest in the origins of framing effects and prospect theory in current times.

Although some systematic literature reviews on framing effects in specific domains have been published in the last decade,[21,22] as far as the search we have conducted in the field of applied social sciences is concerned, no bibliometric analyses on the framing effect have been published so far, thus evidencing the originality of this research.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK: PROSPECT THEORY AND FRAMING EFFECTS

To understand framing effects and its origins, it is necessary to understand prospect theory. In a ground-breaking article, Kahneman and Tversky[6] challenged expected utility theory by showing, in a series of empirical vignette problems involving choices between risky prospects, that people’s preferences are inconsistent with many of the tenets of expected utility theory. In expected utility theory, the utility of a risky prospect is equal to the expected utility of its outcomes, that is, the weighted average of the utilities of each possible outcome multiplied by its respective probability. Kahneman and Tversky[6] developed a descriptive model of individual decision-making under risk that accommodates the patterns of preferences that violate traditional expected utility theory, which they called Prospect Theory (PT).

At the core of PT is the value function, which incorporates three principles. First, the value function has a reference point that divides the space into losses or gains. Unlike expected utility theory, which considers absolute states of wealth parting from zero, prospect theory posits that people assign utility in terms of gains or losses relative to a reference neutral point, which can be, for instance, the status quo (e.g., their current state of wealth). Thus, the domain of the value function is divided into a negative region of losses and a positive region of gains. Second, the value curve assumes diminishing sensitivities, such that marginal gains or losses have less impact when they are more distant from the reference point, implying that, say, a gain of $100 leads to greater satisfaction when wealth is increased from $10 to $110 than from$1000 to $1100, and a loss of $10 kicks in stronger when wealth decreases from $10 is from -$10 to -$110 than from -$1000 to -$1100. Therefore, the value function is S-shaped, concave in the domain of gains, and convex in the domain of losses. Finally, the third and perhaps most important principle (to understand framing effects) is that the value curve is steeper in the domain of losses than in the domain of gains. This implies that outcomes that are encoded as losses are more painful than equal-sized gains are pleasurable. In Kahneman and Tversky’s[6] (p. 279) words, ‘‘losses loom larger than gains.’’ As a result, people are risk averse in choices involving gains and risk seeking in choices involving losses. For instance, in one pair of problems, whereas in the domain of gains, most people preferred a sure gain of $3,000 over a .8 chance to win $4,000, in the domain of losses, there was a preference reversal, in that most people opted for a .8 chance to lose $4,000 over a sure loss of $ 3,000. In other words, in the domain of gains people preferred the sure option despite its lower expected value (+$3,000 vs. +$3,200), while in the domain of losses, people preferred the risky option, despite its lower expected value (-$3,200 vs. -$3,000).

Based on the reversal of preference for risky prospects according to whether one is in the domain of gain or loss, Tversky and Kahneman demonstrated a violation of the axiom of invariance of expected utility theory. Invariance means that people should be indifferent between options that represent alternative descriptions of the same problem.[5] In their classical ‘Asian Disease Problem’, they subjected people to a decision involving the choice between two alternative programs to combat the outbreak of an Asian disease, expected to kill 600 Americans. The choices differed in risk (sure vs. risky) and in how the message was framed (gain- vs. loss-framed), but the expected outcomes of choices were equivalent: 200 people would live and 400 people would die. However, preferences varied significantly depending on both risk and message framing. When faced with a gain-framed message emphasizing lives saved, subjects preferred the sure (200 people will be saved) relative to the risky option (1/3 chance that 600 will be saved and a 2/3 chance that no one will be saved). In contrast, when exposed to a loss-framed message emphasizing how many would die, subjects preferred the risky (1/3 probability that nobody will die and a 2/3 probability that 600 people will die) over the sure alternative (400 people will die).

Tversky and Kahneman[5] used prospect theory to explain the bias in peoples’ preferences in the Asian disease problem. They posited that the way a problem is framed can lead to different choices because of the characteristics of the value function and the underweighting of probabilities (the decision weight ). When the outcome is framed as gains (e.g., lives saved), the concave shape of the value function contributes to risk aversion and the underweighting of the probabilities of gains contributes to the relative attractiveness of the sure gain. On the other hand, when the same outcome is framed as losses, the convex shape of the value function contributes to risk-seeking behavior, and the underweighting of the probability of loss enhances the attractiveness of the probable, relative to the sure loss.

Spurred by the novelty of both prospect theory and framing effects, empirical work on the framing effect began to flourish in the ensuing years. For instance, Kühberger[7] identified ninety-six theoretical and 136 empirical published papers from 1979 to 1996 on framing effects in problems that dealt with risky decision-making in conditions largely similar to those of Tversky and Kahneman’s original research (i.e., formally identical expected values of the options and identical probabilities and outcomes of losses vs. gains). Although the meta-analysis evidenced an overall and significant framing effect, differences between framing conditions were only small to moderate in size. Concurrently, in this same period, other scholars explored variations of the framing effect, such as in problems that entailed no objectively defined risk. These subsequent works demonstrated that the ‘framing effect’ can occur even in the absence of risk or in choices where probabilities are subjective or ambiguous.[1] For instance, many studies investigated how positively- vs. negatively-framed depictions of the same object affect preferences (e.g., a beef 75% lean vs. 25% fat,[23] a surgery with 90% of dying vs. 10% of surviving).[24] Since Prospect Theory is specifically designed to account for choices involving risk, researchers have explored alternative explanations for framing effects.[3] Consequently, the period after Tversky and Kahneman’s[5] paper on framing effects flourished with alternative and/or complementary explanations for the framing effect. Other cognitive and motivational psychological mechanisms, such as the way the information is encoded in memory, salience of desirable vs. undesirable outcomes, and negativity bias were used in addition to prospect theory’s loss aversion.[1,7,25,26] Also, other theories were proposed, such as Venture Theory[27] and Fuzzy-Trace Theory.[28] In sum, although originally conceived as preferences for risk avoidance or risk-seeking when the same choice was framed differently in terms of positive or negative outcomes, respectively, framing effects were later shown to exist regardless of risk, requiring additional cognitive and motivational psychological mechanisms to explain differential judgments and preferences between different presentations of factually equivalent information.

METHODOLOGY

The main objective of this paper is to map the intellectual and conceptual structures of research on framing effects, and how these have evolved over time. The intellectual structure presents the developmental history of a research topic across time and the thematic focus of the key contributors in the field.[29] It is related to which authors, documents, or sources have had a major influence on the academic field.[30] To achieve these objectives, we performed a bibliometric analysis of the literature on framing effects in the past two decades comprising the period from 2001 to 2020. Bibliometric analysis helps in identifying the important structures of a research field, such as networks of researchers, topics, journals, key themes, and emerging topics of research.[31] Specifically, we conducted co-citation analysis, which is the preferred method when the objective is to uncover relationships among cited publications on a scientific field to unveil clusters that represent common themes within the scientific literature of the construct or domain under analysis.[16,32] Co-citation is defined as the frequency with which two units of analysis (e.g., document, author, journal) are cited together, and assumes that the more two items are cited together, the more likely it is that their content is related.[16,32] According to Donthu et al.,[31] co-citation analysis uses co-citation counts to build similarity matrices that serve as inputs to analytical techniques such as factor or cluster analysis to derive thematic clusters that “shed light on the major themes underpinning the intellectual structure in the research field” (p. 291).

Because one of the objectives of the current bibliometric study, as presented earlier, is to analyze how the intellectual structure of the field has developed over time, we divided the sample into periods of up to 10 years, to enable a temporal analysis of the intellectual structure of framing effects and its thematic evolution, as recommended in the literature.[33,34]

To conduct the co-citation analysis, we followed the steps recommended by Zupic and Cater.[16] We first researched which search term would be the most suitable to cover the origin of the framing effect theory and its ramifications in the literature. We conducted a search using solely the search term “framing effect” in both scientific indexing databases, Scopus and Web of Science. Scopus and Web of Science are suitable databases to perform bibliometric analysis, as they provide automatically organized metadata from the research sample, in addition to being rich databases for the large area of Applied Social Sciences.[16] Our judgment, based on the first author’s knowledge of the subject (his doctoral dissertation was on goal framing effect, in which he conducted a traditional literature review) was that the results were comprehensive and qualitatively encompassed all the known developments on the subject.

With the search term validated, we moved to the second stage of compiling the bibliometric data. We applied a first filter by study areas, considering only “Business, Management, and Accounting”, “Decision Science”, “Economics, Econometrics, and Finance”, “Environmental Science”, “Multidisciplinary”, “Psychology”, and “Social Science”. In the document type field, we selected “Articles”. In addition, two filters with the selection of different periods were activated, the first from 2001 to 2010 and the second from 2011 to 2020, allowing different analyses, one for each period, following bibliometric analysis guidelines for temporal range cutoffs of a maximum of ten years.[33] In the end, the database resulted in 312 articles for the period 2001 to 2010 and 823 articles for the period 2011 to 2020. Thus, the total sample consists of 1,135 articles spanning the two decades.

An overlap analysis was then performed to examine the sample composition of the two scientific indexing databases (Scopus and Web of Science). This analysis identified that 98.3% of the total sample was contained in the Scopus database. Because the organized metadata of the Scopus and Web of Science databases are not automatically compatible, and because it is unlikely that a small number of documents exclusive to the Web of Science database (only 1.7% of the sample) would affect the formation of clusters, we decided to use only the documents from the Scopus database. With the database extracted from Scopus for the last two decades (2001 to 2010 and 2011 to 2020), we executed the procedures in the Bibexcel software.[35] Bibexcel takes raw bibliographic data (e.g., an export from Scopus), and calculates the similarity matrices between items (documents, authors, journals, words).[16] As a result of correction procedures, out of a total of 54,979 references, 6,771 were corrected and 407 were deleted as they were documents on methodology. Among the processes carried out in Bibexcel, the detailed correction of references in the database was essential to achieve a more accurate result,[35] in addition to mitigating the problems of synchronization of references that are critical in bibliometric research.[36] With the corrected bases, we pruned the data by applying Lotka’s bibliometric law, which states that few articles with more citations are representative of the researched subject.[37] This procedure is recommended by Zupic & Cater[16] when conducting co-citation analyses to (i) limit the analyzed set to a manageable size and (ii) ensure that only cited publications that contain enough citation data for analysis are retained. Thus, we established a cutoff point of references with >= 12 citations in the sample of the 2001 to 2010 period, resulting in 59 documents representing 12.38% of the citations in the sample, and a cutoff point of references with >= 19 citations in the sample of the 2011 to 2020 period, resulting in 70 articles representing 7% of the citations in the sample.

The next step was to perform the analysis of the data and derive the main clusters with a dimensionality reduction technique. To this end, we employed Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) with Principal Components Analysis (PCS) as an extraction method to identify the scholarly subfields in the literature on framing effects. The principal component analysis is one of the most frequently used techniques for finding subgroups in bibliometric studies.[16] EFA needs a similarity matrix of documents as an input for Statistical Software (SPSS). Thus, the bibliometric software Bibexcel was employed to produce a co-occurrence frequency matrix in which the elements of the matrix are co-citations called “similarity co-citation matrix”.[16] The co-citation similarity matrix corresponds to the references between samples “A” and “B” that are the same.[30] When we completed the procedures in the Bibexcel software, the similarity co-citation matrix was ready to perform the principal component analysis in the SPSS statistical software.[38] We then performed data reduction with principal component analysis and the Varimax rotation extraction method with Kaiser normalization. The PCA analysis resulted in three subgroups and led to the creation of a new square matrix, which was used to develop the network diagram and centrality analysis using Ucinet and Netdraw software.[39] Centrality refers to the number of relational ties an article has in a network and quantifies its importance (number of links) in a network.[16] The shortest average path length indicates the centrality of a node in the network between it and other nodes in the network.[30] In addition, density and cohesion analyses were developed with the support of the Excel spreadsheet. Density refers to the distinctiveness of a factor within the network. Its calculation considers the number of existing ties and the total number of possible ties within the same factor. As a bibliometric indicator, density reflects the extent to which various flows within a research subfield pursue their agendas on a shared basis.[30] On the other hand, cohesion relates the density of a factor to its interconnectedness with the others. Highly cohesive groups are those in which its members are densely interconnected within the group but thinly connected to members of other groups. In bibliometric applications, the cohesion measure indicates the extent to which a research subfield follows an agenda independent of other discourses.[30]

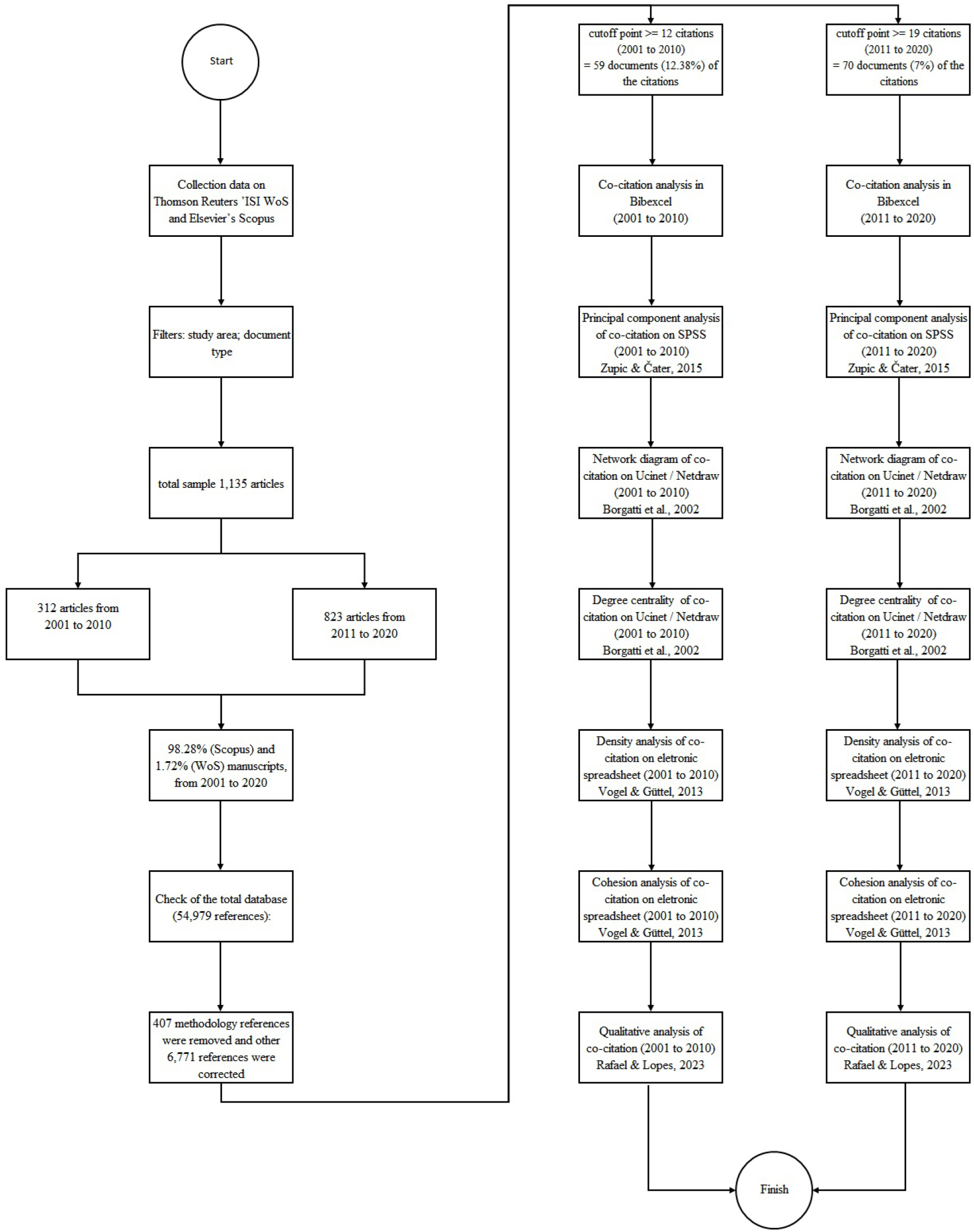

At the end of the statistical analysis phase, we began the execution of the qualitative analyses. Initially, all manuscripts resulting from the co-citation analysis were downloaded and read by the authors. In a spreadsheet, the sample (manuscripts) were organized describing factors such as title, abstract, keywords, research objective, the method used, main theoretical and practical contributions to the literature, analyzed constructs and possibilities for future studies.[40] The objective of this phase was to find the nature of the composition of each factor resulting from the co-citation analysis. Then, two of the three authors carried out the analysis separately and at the end, the results were compared. For non-convergent cases, the two researchers met to reach a consensus. At the end of this phase, it was possible to name the factors and characterize them, each with its importance for the literature. The flowchart with data selection and analysis procedures is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Flowchart of data selection and analysis procedures.

RESULTS

We report the results of our co-citation analysis in two sections. In the first section, we present the quantitative analysis. For each period of analysis, we present the number and composition of the factors derived from the principal component analyses. We also present the network diagrams and analyses of centrality, density, and cohesion for both periods of the research. Then, in the second section, we introduce a qualitative analysis, providing a more detailed discussion of the main authors and their works in each factor. As will be discussed, three factors were common to both periods of analysis. Also, there was considerable overlapping of authors and papers in both periods of analysis. To avoid redundancy, we decided to collapse the qualitative analysis of both periods into one single subsection, highlighting, whenever appropriate, when authors and their works appear specifically in one period.

Quantitative Analysis

Period 2001-2010

The principal component analysis for the period 2001 to 2010 resulted in 3 factors comprising 49 references. All statistical indicators, presented in Table 1, are adequate according to the literature.[38] We named each factor based on the composition and thematic communalities of articles that form each one, as detailed in Table 1. The first factor was named “Expanding the framing effect” and is formed by 25 references. The centrality analysis, which identifies the most important reference in each factor (Table 2), revealed that Levin et al.’s[1] article stands out as the central article in this factor. The second factor was named “The framing effect in Communication: Media, Politics and Public Opinion” and is composed of 17 references. The work with the greatest centrality is that of Iyengar.[41] The third factor was titled “The framing effect in decisions about health and treatments” and comprises seven articles, with Meyerowitz and Chaiken[42] as the central article in this factor.

| Rotated Component Matrix – Co-citation – 2001-2010 | GR KMO: .773 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Articles | 1 | 2 | 3 | Ind. KMO | Com. |

| 1 | Bless et al.[43] | .926 | -.003 | .052 | .701 | .862 |

| 1 | Takemura[44] | .922 | -.138 | .090 | .876 | .878 |

| 1 | Miller & Fagley[45] | .920 | -.129 | .104 | .701 | .875 |

| 1 | Schneider[46] | .911 | -.164 | .164 | .773 | .884 |

| 1 | Sieck & Yates[47] | .905 | -.113 | .110 | .828 | .845 |

| 1 | Wang et al.[48] | .884 | -.207 | .090 | .720 | .834 |

| 1 | Wang[49] | .884 | -.040 | .277 | .748 | .860 |

| 1 | Jou et al.[50] | .865 | -.052 | .073 | .745 | .758 |

| 1 | McElroy & Seta[51] | .862 | -.194 | .086 | .883 | .789 |

| 1 | Levin et al.[52] | .856 | -.134 | .352 | .725 | .876 |

| 1 | Frisch[53] | .851 | -.001 | .254 | .818 | .790 |

| 1 | Fagley & Miller[54] | .847 | -.025 | .290 | .751 | .803 |

| 1 | Kühberger[25] | .834 | .032 | .286 | .897 | .779 |

| 1 | Von Neumann & Morgenstern[55] | .834 | -.112 | .218 | .873 | .755 |

| 1 | Smith & Levin[56] | .820 | -.177 | .334 | .900 | .815 |

| 1 | Fagley & Miller[57] | .812 | -.081 | .205 | .863 | .708 |

| 1 | Simon et al.[58] | .808 | -.231 | .092 | .695 | .715 |

| 1 | Mcneil et al.[59] | .803 | -.112 | .427 | .695 | .840 |

| 1 | Kahneman & Tversky[6] | .802 | -.129 | .392 | .884 | .814 |

| 1 | Kühberger et al.[60] | .762 | .055 | .165 | .756 | .612 |

| 1 | Kühberger[7] | .762 | -.016 | .415 | .773 | .753 |

| 1 | Fagley & Miller[61] | .748 | -.142 | .270 | .723 | .654 |

| 1 | Levin et al.[1] | .711 | -.099 | .362 | .853 | .647 |

| 1 | Kahneman & Tversky[62] | .633 | .180 | .414 | .865 | .606 |

| 1 | Thaler[63] | .608 | .031 | .503 | .876 | .624 |

| 2 | Kinder & Sanders[64] | -.116 | .928 | -.056 | .693 | .878 |

| 2 | Nelson & Kinder[65] | -140 | .922 | -.062 | .816 | .874 |

| 2 | Cappella & Jamieson[66] | -.117 | .922 | -.036 | .759 | .866 |

| 2 | Entman[67] | -.031 | .920 | -.055 | .814 | .851 |

| 2 | Nelson & et al.[68] | -.063 | .916 | -.069 | .726 | .848 |

| 2 | Zaller[69] | 0.00 | .890 | -.083 | .803 | .800 |

| 2 | Nelson et al.[70] | -.073 | .888 | -.085 | .672 | .802 |

| 2 | Druckman[71] | -.047 | .876 | -.050 | .728 | .772 |

| 2 | Gamson[72] | -.109 | .869 | -.024 | .724 | .768 |

| 2 | Druckman & Nelson[73] | -.053 | .867 | -.068 | .658 | .760 |

| 2 | Druckman[74] | -.019 | .866 | -.059 | .870 | .754 |

| 2 | Nelson & Oxley[75] | -.144 | .863 | -.085 | .639 | .774 |

| 2 | Price & Tewksbury[76] | -.154 | .855 | .012 | .862 | .756 |

| 2 | Sniderman & Theriault[77] | -.007 | .845 | -.102 | .652 | .725 |

| 2 | *Iyengar[41] | -.099 | .823 | -.019 | .744 | .688 |

| 2 | Price et al.[78] | -.162 | .804 | -.019 | .825 | .674 |

| 2 | Eagly & Chaiken[79] | .021 | .802 | .265 | .596 | .714 |

| 3 | Banks et al.[80] | .351 | -.094 | .803 | .866 | .778 |

| 3 | Maheswaran & Meyers-Levy[81] | .344 | -.098 | .802 | .803 | .772 |

| 3 | Rothman et al.[82] | .362 | -.190 | .782 | .718 | .779 |

| 3 | Levin[83] | .514 | .050 | .717 | .785 | .782 |

| 3 | Rothman & Salovey[26] | .564 | -.044 | .691 | .867 | .799 |

| 3 | *Meyerowitz & Chaiken[51] | .547 | -.118 | .680 | .754 | .777 |

| 3 | Levin & Gaeth[23] | .614 | -.041 | .668 | .748 | .826 |

| Number of articles by factor | 25 | 17 | 7 | |||

| Composite reliability – Cronbach’s Alpha | 96.87 | 97.53 | 93.14 | |||

| TVE – RSSL – % | 38.59 | 27.52 | 11.90 | |||

| TVE – RSSL – Cumulative % | 38.59 | 66.10 | 78.00 | |||

The network diagram of the period 2001-2010 (Figure 2) suggests there is huge heterogeneity, especially between factors 1 and 3. In other words, cluster 2 in the network is quite disconnected and independent from the other two. Table 2 presents the results of cohesion and density analyses. There is a high density of factors, that is, the references belonging to a factor frequently interact within the factor. Cohesion analysis is linear between factors, with a high relationship between factors.

Figure 2:

Co-citation network diagram – 2001-2010.

| Total Centrality | Density and Cohesion Index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Variable | Degree | nDegree | Factor | Density | Cohesion |

| 1 | Levin et al.[1] | 546 | 0.223 | 1 | 91.33% | 1.277 |

| 2 | Iyengar[41] | 283 | 0.116 | 2 | 98.53% | 1.510 |

| 3 | Meyerowitz & Chaiken[42] | 232 | 0.095 | 3 | 100.00% | 1.510 |

Period 2011-2020

The principal component analysis for the period from 2011 to 2020 generated four factors, one more compared to the previous decade, comprising 62 references. All statistical indicators are adequate according to the literature,[38] and are presented in Table 3. The first three factors are thematically equivalent to the factors of the period 2001-2010, mainly differing in size and composition of works. Factor 1 (Expanding the framing effect) is formed by 25 references, of which 11 are common to the previous period. Centrality analysis indicates that Kahneman and Tversky’s[6] article on prospect theory is central to Factor 1. Factor 2 (The framing effect in Communication: Media, Politics and Public Opinion) is composed of 21 references, of which 10 are common to the previous period. The main work in this factor is the article by Entman.[67] Factor 3 (The framing effect in decisions about health and treatments) is composed of 11 references, of which 3 are common to the previous period. Central to this factor is the article by Rothman and Salovey.[26] Finally, the fourth factor, exclusive to this period, was named “The origins of the framing effect: classic articles by Tversky and Kahneman”, and is composed of five references. As expected, Tversky and Kahneman[5] appear as the article with the highest centrality.

| Rotated Component Matrix – Co-citation – 2011-2020 | GR KMO: .742 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Articles | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Ind. KMO | Com. |

| 1 | Wang[49] | 0.935 | -0.009 | 0.135 | 0.164 | 0.911 | 0.919 |

| 1 | LeBoeuf & Shafir[84] | 0.921 | 0.002 | 0.124 | 0.150 | 0.780 | 0.886 |

| 1 | Miller & Fagley[45] | 0.911 | 0.010 | 0.129 | 0.232 | 0.848 | 0.901 |

| 1 | Gonzalez et al.[85] | 0.905 | -0.064 | 0.135 | 0.180 | 0.791 | 0.873 |

| 1 | Frederick[86] | 0.904 | -0.029 | 0.070 | 0.163 | 0.783 | 0.849 |

| 1 | Kühberger[25] | 0.900 | -0.030 | 0.186 | 0.192 | 0.758 | 0.883 |

| 1 | Levin et al.[52] | 0.894 | -0.050 | 0.288 | 0.171 | 0.809 | 0.913 |

| 1 | De Martino et al.[87] | 0.892 | 0.020 | 0.245 | 0.113 | 0.784 | 0.868 |

| 1 | Peters & Levin[88] | 0.890 | -0.032 | 0.082 | 0.182 | 0.681 | 0.833 |

| 1 | Peters et al.[89] | 0.886 | 0.070 | 0.060 | 0.154 | 0.688 | 0.816 |

| 1 | Reyna & Brainerd[28] | 0.880 | -0.144 | 0.080 | 0.126 | 0.805 | 0.818 |

| 1 | Kühberger et al.[60] | 0.874 | 0.038 | 0.177 | 0.008 | 0.853 | 0.796 |

| 1 | Loewenstein et al.[90] | 0.864 | 0.129 | 0.093 | 0.142 | 0.737 | 0.791 |

| 1 | Mcneil et al.[59] | 0.863 | 0.002 | 0.365 | 0.173 | 0.792 | 0.908 |

| 1 | Kühberger[7] | 0.851 | 0.036 | 0.326 | 0.113 | 0.889 | 0.844 |

| 1 | Kühberger & Tanner[91] | 0.843 | -0.093 | 0.160 | -0.019 | 0.787 | 0.745 |

| 1 | *Kahneman & Tversky[6] | 0.833 | 0.032 | 0.298 | -0.259 | 0.675 | 0.852 |

| 1 | Druckman & Mcdermott[92] | 0.833 | 0.225 | 0.155 | -0.024 | 0.771 | 0.769 |

| 1 | Levin & Gaeth[23] | 0.796 | 0.137 | 0.381 | 0.177 | 0.720 | 0.829 |

| 1 | Tversky & Kahneman[93] | 0.795 | 0.132 | 0.349 | 0.269 | 0.774 | 0.843 |

| 1 | Levin et al.[1] | 0.79 | 0.079 | 0.336 | 0.121 | 0.739 | 0.758 |

| 1 | McElroy & Seta[51] | 0.786 | -0.149 | 0.396 | 0.228 | 0.817 | 0.849 |

| 1 | Thaler[63] | 0.768 | 0.027 | 0.322 | 0.315 | 0.822 | 0.793 |

| 1 | Baumeister et al.[94] | 0.725 | 0.176 | 0.406 | 0.306 | 0.846 | 0.815 |

| 1 | Thaler & Sunstein[95] | 0.691 | -0.022 | 0.409 | 0.345 | 0.842 | 0.765 |

| 2 | Borah[96] | 0.036 | 0.936 | 0.047 | 0.024 | 0.651 | 0.879 |

| 2 | Iyengar[41] | -0.165 | 0.932 | -0.045 | -0.012 | 0.620 | 0.897 |

| 2 | Sniderman & Theriault[77] | 0.011 | 0.923 | -0.069 | -0.015 | 0.750 | 0.856 |

| 2 | Nelson et al.[68] | -0.064 | 0.916 | -0.045 | 0.043 | 0.720 | 0.848 |

| 2 | Slothuus[97] | -0.079 | 0.914 | -0.101 | -0.060 | 0.825 | 0.855 |

| 2 | Price et al.[78] | -0.012 | 0.906 | 0.008 | -0.046 | 0.602 | 0.823 |

| 2 | Nelson et al.[70] | -0.031 | 0.902 | -0.031 | -0.017 | 0.635 | 0.816 |

| 2 | Chong & Druckman[98] | 0.010 | 0.902 | -0.057 | 0.005 | 0.610 | 0.817 |

| 2 | Price & Tewksbury[76] | -0.139 | 0.896 | -0.023 | 0.080 | 0.695 | 0.829 |

| 2 | Nelson & Kinder[65] | 0.117 | 0.894 | 0.017 | 0.011 | 0.614 | 0.814 |

| 2 | Scheufele & Tewksbury[99] | -0.063 | 0.890 | 0.040 | 0.003 | 0.712 | 0.797 |

| 2 | Druckman[74] | 0.229 | 0.888 | 0.064 | 0.014 | 0.776 | 0.846 |

| 2 | Druckman[71] | 0.023 | 0.887 | -0.026 | 0.088 | 0.574 | 0.796 |

| 2 | Chong & Druckman[100] | -0.049 | 0.883 | -0.079 | -0.068 | 0.602 | 0.793 |

| 2 | Gamson & Modigliani[101] | 0.071 | 0.879 | 0.029 | -0.112 | 0.793 | 0.792 |

| 2 | Scheufele[102] | -0.085 | 0.874 | 0.035 | 0.080 | 0.844 | 0.778 |

| 2 | Druckman & Nelson[73] | 0.005 | 0.859 | -0.048 | 0.057 | 0.570 | 0.743 |

| 2 | Druckman[103] | 0.165 | 0.854 | 0.035 | -0.004 | 0.798 | 0.758 |

| 2 | Chong & Druckman[104] | 0.142 | 0.853 | 0.035 | -0.003 | 0.697 | 0.750 |

| 2 | Goffman[105] | 0.175 | 0.847 | 0.110 | -0.111 | 0.669 | 0.772 |

| 2 | *Entman[67] | 0.006 | 0.834 | -0.005 | -0.070 | 0.852 | 0.700 |

| 3 | Rothman et al.[106] | 0.188 | -0.100 | 0.907 | -0.056 | 0.643 | 0.871 |

| 3 | Rothman et al.[107] | 0.169 | -0.032 | 0.893 | -0.070 | 0.590 | 0.832 |

| 3 | O’Keefe & Jensen[108] | 0.132 | 0.003 | 0.848 | 0.207 | 0.649 | 0.779 |

| 3 | O’Keefe & Jensen[109] | 0.231 | -0.095 | 0.842 | 0.188 | 0.686 | 0.807 |

| 3 | Rothman et al.[83] | 0.357 | -0.082 | 0.812 | -0.036 | 0.636 | 0.794 |

| 3 | Maheswaran & Meyers-Levy[81] | 0.417 | 0.048 | 0.794 | 0.268 | 0.768 | 0.879 |

| 3 | Lee & Aaker[110] | 0.351 | -0.008 | 0.788 | 0.083 | 0.831 | 0.750 |

| 3 | *Rothman & Salovey[26] | 0.461 | 0.013 | 0.779 | 0.040 | 0.797 | 0.822 |

| 3 | Meyerowitz & Chaiken[42] | 0.520 | -0.044 | 0.750 | 0.166 | 0.849 | 0.862 |

| 3 | Higgins[111] | 0.387 | 0.110 | 0.634 | 0.228 | 0.763 | 0.616 |

| 3 | Chaiken[112] | 0.419 | 0.394 | 0.473 | 0.321 | 0.810 | 0.657 |

| 4 | Tversky & Kahneman[20] | 0.447 | -0.103 | 0.174 | 0.822 | 0.778 | 0.917 |

| 4 | Tversky & Kahneman[113] | 0.470 | -0.003 | 0.058 | 0.821 | 0.690 | 0.898 |

| 4 | Tversky & Kahneman[19] | 0.301 | -0.058 | 0.285 | 0.814 | 0.817 | 0.838 |

| 4 | *Tversky & Kahneman[5] | 0.439 | 0.010 | 0.278 | 0.773 | 0.643 | 0.869 |

| 4 | Tversky & Kahneman[17] | 0.470 | -0.014 | 0.048 | 0.714 | 0.655 | 0.733 |

| Number of articles by fator | 25 | 21 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Composite reliability – Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.957 | 0.977 | 0.954 | 0.671 | |||

| TVE – RSSL – % | 33.28 | 27.48 | 13.97 | 7.20 | |||

| TVE – RSSL – Cumulative % | 33.28 | 60.76 | 74.73 | 81.93 | |||

The factors are linear regarding the cohesion of the period between 2011 and 2020, except for factor 4, represented by the articles by Tversky and Kahneman, which has a low cohesion, that is, the articles of this factor frequently interact with the other factors. This can be explained by the importance of the authors regarding the common theme (framing effect) that permeates the other three factors (Table 4). The low cohesion of factor 4 can also be observed by the factor heterogeneity observed in the network diagram (Figure 3). Regarding density, the exception is also found in Factor 4, being only 10%, much smaller compared to the other factors. This can be explained by the fact that the authors, Tversky and Kahneman, use their works as a basis for the five articles that comprise this factor, therefore, there is not much citation interaction between them.

Figure 3:

Co-citation network diagram-2011-2020.

| Total Centrality | Density and Cohesion Index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Manuscript | Degree | nDegree | Factor | Density | Cohesion |

| 1 | Kahneman and Tversky[6] | 1,005 | 0.127 | 1 | 88,50% | 1,647 |

| 2 | Entman[67] | 474 | 0.060 | 2 | 98,33% | 2,228 |

| 3 | Rothman and Salovey[26] | 247 | 0.031 | 3 | 94,55% | 1,700 |

| 4 | Tversky and Kahneman[1] | 1.174 | 0.148 | 4 | 10,00% | 0,140 |

Qualitative Analysis

This section is dedicated to the qualitative analyzes derived from the detailed reading of the references obtained through exploratory quantitative factor analysis. Because our interpretation of the factors indicated that three of them were common to both periods of analysis, we discuss both periods together, highlighting, when necessary, when scholars or works are more prominent in or exclusive to one specific factor.

Factor 1: Expanding the framing effect

Factor 1, in the two decades, is composed of research that develops the theory of framing effect from the original works of Tversky and Kahneman, advances its understanding, and tests the framing effect in other contexts. These are works that seek to test, validate, or even confront the findings of Tversky and Kahneman, both in theoretical and empirical articles. Mostly, what these papers have in common is that they extend Kahneman and Tversky’s framing effects to judgments and decisions in which expected values are not quantifiable and do not necessarily involve risk. As a result, framing effects have been expanded to explain decisions between equivalent options that differ in dimensions other than the levels of risk between alternatives. And, as a consequence, theories other than Prospect Theory have been used to explain the differential preferences of individuals for equivalent options.

The centrality analysis identifies the most important references in each factor for each period (Tables 3 and 4). In the decade 2001-2010, Levin et al.’s article[1] stands out as the central article in factor 1. In this important paper, the authors addressed contradictory and equivocal findings from the literature by developing a taxonomy of three frame types and discussed the mechanisms and theories underlying each type of frame. In addition to Tversky and Kahneman’s[5] risky-choice framing, the type most associated with the term “framing”, Levin et al.[1] proposed two other types of framing: attribute framing and goal framing. In attribute framing, the focus of Levin’s works,[23, 83,114] an attribute of an object or event is the focus of framing manipulation, in which either one of the complementary percentages of “success” or “failure” is presented. The relevance of the research by Irwin P. Levin and colleagues[23, 92,114] spanned both periods of analysis. It consistently showed that consumers’ evaluations of the same product (e.g., ground beef that is 75% lean and 25% fat) were more favorable when the product was presented in terms of its positive attribute label (e.g., 75% lean) than when it was presented in terms of its negative attribute label (e.g., 25% fat). Because decisions involving attribute framing do not involve risks, its effects are explained in terms of more favorable (unfavorable) memory associations of positively (negatively) framing of objectively the same information.[13] These effects have been shown to occur not only in single product-attribute decisions but also in multi-alternative and multi-attribute decisions.[15] In the third type of manipulation – goal framing – the focus of the framing is an action or behavior, and the framing manipulation consists of either highlighting the positive or the negative consequences of engaging or not engaging, respectively. Levin et al.[52] conducted empirical tests of the typology elaborated by Levin et al.,[1] where all three types of framing effects are examined and related to each other using the same subjects in a series of related tasks. In sum, the works of Levin and his colleagues were important because they extended the framing effect to contexts in which decisions do not involve risk and thus could not be explained by prospect theory.

Another important work in this factor in both periods of analysis is that of Richard Thaler,[63] who used prospect theory to develop his theory of ‘mental accounting’ to explain biases in the way people treat money and evaluate transactions, depending on factors such as its origin and its use. One major contribution of his work is that the way we perceive losses and gains depends on whether they are integrated or segregated. People are generally happiest when gains are obtained in separate events (segregated) and when losses are suffered all at once (integrated), even when the separate and joint events amount to the same outcome. In other words, the way gains or losses are framed, either jointly or separately, influences people’s preferences. Thaler[63] shows that people’s behaviors toward money violate the economic principle of fungibility, that is, money should be fungible since a dollar is worth the same no matter where it comes from. In mental accounting, however, people put ‘labels’ into money, and allocate money differently depending on its origin or how it is spent.

Appearing more in the first decade analyzed (2001 to 2010), Reyna and Brainerd[28] developed the Fuzzy-Trace Theory, arguing that individuals form two types of mental representations about a past event, called essential traits and literal traits. Essential features are diffuse representations of a past event, while literal features are detailed representations of a past event. Although people can process both essential and literal information, they prefer to reason with essential traits, coinciding with the thoughts of Tversky and Kahneman. Also, according to Fuzzy-trace theory, individuals are more likely to process information on the most superficial and simple level, simplifying quantitative information to its qualitative gist. So, for instance, the information that 200 people will be saved, as in Tversky and Kahneman’s[5] classic Asian Disease Problem, might be simplified into “some people will be saved.” This theory can be classified as a cognitive model among several models that study framing effects.[115]

Another prominent scholar in this factor is Anton Kühberger. Kühberger[25] suggests that framing research can yield more results if researchers adopt a more cognitive point of view. According to Kühberger, Prospect Theory[6] is not as thorough as a cognitive theory about judgment and decision-making. The Fuzzy-Trace Theory,[28] and to a greater degree, the Probabilistic Mental Model,[116] is more promising, as its predictions are supported by ideas related to information processing and cognitive functioning. His meta-analysis of framing effects[7] showed that the framing effect is a reliable phenomenon, but that salience manipulations of results need to be distinguished from reference point manipulations and that the procedural features of experimental setups have a considerable impact on the size of effects in framing experiments. A second meta-analysis of studies that employed Tversky & Kahneman’s[5] Asian disease problem revealed that risk preference depends on the size of rewards, probability levels, and the type of asset at stake (money/property x human lives). In summary, deficiencies of formal theories are identified, such as Prospect Theory,[6] Cumulative Prospect Theory,[20] Utility Theory,[117] and Venture Theory.[27] Finally, in a more recent article, Kühberger & Tanner,[91] make a comparison between the Prospect Theory and the Fuzzy-Trace Theory, indicating that the latter is more suitable for certain cases involving risky options.

Finally, the works of Paul Miller and N.S. Fagley also contributed to this factor, especially in the first period analyzed. These scholars conducted several replications of the framing effects, and investigated some potential boundary conditions. Specifically, they studied the influence of contextual and personal variables as moderators of the framing effect. The results of their studies are mixed. For instance, one of their first studies[54] examined whether formal training in statistical decision theory and thus the development of skills for rational decision-making would eliminate the framing decision bias. Surprisingly, although the results replicated Tversky and Kahneman[5] in the positively framed problem, they did not find differences in choices between risky and sure options in the negatively framed problem, neither before nor after the training. One explanation was that participants had to provide a rationale for their choices, which may have worked as an incentive for participants to cognitively deliberate on the expected values of the outcomes and conclude that both options were equivalent. In a subsequent investigation, it was found, indeed, that asking people to provide a reason for their choice affected the results, in that the framing effect only occurred when no rationale was requested.[45] Another contribution of their work is that people are sensitive to the probability of success in the risky option, such that the greater the probability of success, the more the risky option is chosen. Another important moderator investigated by the authors was the “outcome arena,” such that people make riskier choices when outcomes involved human lives, compared to money.[54] Finally, their research also showed significant differences between genders, such that the framing effect is stronger for females than males.[54,57]

Factor 2: the framing effect in communication: media, politics, and public opinion

Factor 2 has as its main characteristic articles that verify and analyze the framing effect in communications, especially regarding how the way information is presented impacts public opinion. In this factor, the work with the greatest centrality is Shanto Iyengar’s book Is anyone responsible?: How television frames political issues,[41] in which he explored the role of television news in agenda setting. Agenda setting refers to the selection of some stories over others by news editors in terms of what is newsworthy or not. As a consequence, the news media, by virtue of their selective coverage of particular problems and public issues, can lead audiences to consider what is more or less important to make judgments. Thus, for instance, in the political arena, if the media deems unemployment as more newsworthy, voters can be induced to judge candidates in terms of their plans to deal with unemployment. The author explores the impact of television’s impact on public opinion and causal attributions of responsibility that result from how news formats are framed as either episodic or thematic. Episodic news frames depict issues in terms of specific instances, such as a terrorist bombing or a homeless person, without considering the broader context. In contrast, thematic framing depicts issues in a more general framing, such as reports on the antecedents of terrorism. Iyengar argues that episodic framing predominates in television political news coverage, and based on experimental research, he demonstrated that episodic framing encourages viewers to blame society’s problems on individuals rather than social and political institutions such as Congress or political parties.[41,118] The author also concludes that thematic framing has the opposite effect. As television news emphasizes episodic framing, it shifts the blame from the government’s problems, resulting in a weakening of political accountability.

Two other important scholars that appear in this factor are Vincent Price and David Tewksbury. Drawing from the tenets of framing effects set forth by Iyengar,[41] they propose a theoretical account of how agenda-setting, priming, and framing effects activate knowledge and influence the evaluation of political and other stimuli.[76] The model contains three basic elements: knowledge store, current stimuli, and active thought. Priming – the tendency of audience members to evaluate political leaders based on what the news media selects (i.e., agenda setting) – and issue-framing effects, that is, the way stories are produced and presented, affect audience activation of thoughts and influence evaluations via an intermediate impact on knowledge activation. In a subsequent work, Price, Tewksbury and Powers[78] illustrated, in two experimental studies, the knowledge activation potential of news story frames. A core story about cuts in state funding to the university was complemented by paragraphs containing different frames based on what they called “news values” (conflict, human interest, and consequence). Their results revealed that participants generated more thoughts related to each frame when they read the core story complemented by the respective frame (e.g., thoughts related to conflict in the conflict frame).

Another work that represents this factor well is Robert Entman’s Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm.[67] The author argues against the notion that the field of Communication lacks disciplinary status, and, quite the opposite, can aspire to become a discipline/science, insofar as it synthesizes related theories and concepts that “would otherwise remain scattered in other disciplines” (p. 51). The author uses the framing effect, based on the ideas of Tversky and Kahneman, as a case study for his proposition, stating that the concept of framing consistently offers a way to describe the power of a text in communication. Entman[67] (p. 51) claims that the analysis of the framing effect “illuminates the precise way in which the influence on a human consciousness is exerted by the transfer (or communication) of information from a place – such as speech, report, or novel – to that consciousness.”

Another prominent scholar on this factor is Thomas E. Nelson. In the examination of group-centrism and public opinion, Nelson and Kinder[65] showed that group-centrism depends in part on how issues are framed in public debates. When issues are structured in such a way as to draw attention to the beneficiaries of a policy, group-centrism increases, and when issues are structured in such a way as to divert the attention of beneficiaries, group-centrism decreases. In a subsequent paper, Nelson et al.[68] investigated the framing effect in the relationship between attitudes towards the poor and opinions about well-being, showing how the mass media can profoundly influence public opinion, even without any clear attempt at persuasion or manipulation. In another influential article, Nelson et al.[70] investigated the framing effect on tolerance of the Ku Klux Klan. In the experiments, participants were introduced to two news contexts, one showing a presentation of the Ku Klux Klan as a manifestation of freedom of expression and the other, as a manifestation of the disturbance of public order. The results show that the participants who were presented with the first scenario showed more tolerance than those from the other group.

Another scholar who stands out in this factor is James Druckman, who studied framing effects on public opinion. Druckman[71] argues that the framing effect must be better understood by academics and analyzes its impacts, positive and negative, on the formation and construction of citizenship skills. Along the same lines, in his 2001 article On the Limits of Framing Effects, Druckman[74] argued that framing effects are generally seen as evidence that elites manipulate citizens unilaterally, who uncritically accept whatever scenario they hear. However, he showed that there is a certain limit to the framing effect. The credibility of the perceived source is a prerequisite for there to be a framing effect and such an effect may occur not because elites seek to manipulate citizens, but because citizens systematically and wisely choose credible elites for guidance, not configuring signal manipulation. Shortly after, Druckman and Nelson[73] discuss the influence of elite rhetoric and interpersonal conversations on citizens’ opinions and how interpersonal conversations affect past elite frame effects. They find that conversations that include only common perspectives do not affect the framing effect coming from the elite, but conversations that include conflicting perspectives eliminate such effects.

As they are more recent, the studies by Dennis Chong, in collaboration with James Druckman only appeared in the last decade analyzed. Chong & Druckman[100] investigate the effect of democratic competition on the power of elites in public opinion, showing that framing effects depend more on the qualities of frames than on their frequency of dissemination and that competition alters but does not eliminate frame influence. Chong & Druckman[98] also investigated how frames function in competitive environments, integrating research on attitude structure and persuasion. Finally, in another paper, Chong and Druckman[104] revisited the meaning of the concept of framing and define approaches to the study of the framing effect in public opinion. Furthermore, they define a method to identify frames in communication and a psychological model to understand how these frames affect public opinion.

Factor 3: the framing effect on health and treatment decisions

Factor 3 is composed of articles that analyze the impacts of the framing effect in decision-making situations related to health issues and disease treatments. The framing effect is also analyzed from the point of view of interactions between medical staff and patients when giving diagnoses or encouraging preventive actions for the health of patients. An influential work on this factor was Meyerowitz and Chaiken’s[42] examination of framing effects on attitudes and behaviors related to breast self-examination, which appeared in this factor in both periods analyzed and was the central work in the first decade. The authors examined whether emphasizing the negative consequences of not performing breast self-examination (“Women who do not do BSE have a decreased chance of finding a tumor in the early, more treatable stage of the disease”; negative framing), would be more persuasive than emphasizing the focusing on benefits gained by self-examination (“Women who do BSE have an increased chance of finding a tumor in the early, more treatable stage of the disease”; positive framing). The results revealed that women were more persuaded when they received the negatively rather than the positively framed message, although both messages were imbued with factually equivalent information. Meyerowitz and Chaiken justify their findings on the grounds that performing BSE is a risk-seeking behavior, and the different messages change perceptions of a neutral reference point. The positive consequences of performing BSE are encoded as gains relative to a neutral reference point represented by a current belief of being cancer-free. In contrast, the exposure to arguments that emphasize the potential losses inherent in nonadherence may shift the reference point to one of loss, represented by doubts about their health status. Because in the domain of losses people are more risk-seeking, the negatively framed message is more persuasive.

Because Meyerowitz and Chaiken’s[42] findings apparently contradicted those of Levin and Gaeth,[23] Maheswaran and Meyers-Levy,[81] two other influential scholars in this factor in both periods analyzed, proposed a different explanation. They contended that involvement with the issue moderates the framing effect. They proposed that, under high involvement, people process information in more detail, whereas under low involvement conditions, people tend to form attitudes on the basis of simple inferences derived from peripheral cues in the persuasion context. Because negative information receives greater weight (i.e., negativity bias), negatively framed messages should be more persuasive than positively framed ones when involvement, and thus detailed processing, is high. In contrast, when issue involvement is low and information processing is also low, the impact of negative information should be attenuated. In an experiment similar to that of Meyerowitz and Chaiken[42] using a context of blood test to check cholesterol levels to check for susceptibility to heart disease later in life, the authors confirmed their hypothesis.

The works of Alexander Rothman and Peter Salovey were more relevant for Factor 3 in the last decade. In the work titled The Influence of Message Framing on Intentions to Perform Health Behaviors, Rothman et al.,[82] based on Kahneman and Tversky[6] and Meyerowitz and Chaiken,[42] evaluated the influence of the framing effect on the intentions to perform behaviors related to skin cancer prevention treatments. They revealed that negative framing was more efficient than positive framing, but only for women, perceived as having greater involvement in the treatments than men. In another study, Rothman et al.[106] conducted an experiment in the context of gingival disease detection or prevention, which revealed that messages with loss framing are more effective in promoting disease detection behaviors (screening), and messages with gain framing are more effective in promoting health proof behaviors (prevention). Finally, in their investigation of health practices in the cancer treatment process, Rothman et al.[107] revealed that appeals with a gain frame are more effective in directing behaviors that prevent the onset of the disease, while appeals with a loss frame are more effective in directing behaviors that detect the presence of a disease.

Finally, also appearing in the last decade were meta-analyses carried out by Daniel O’Keefe and Jacob Jensen concerning the examination of whether gain- vs. loss-framed messages may differentially influence compliance with health-promoting or disease prevention behaviors. In their first study,[108] a meta-analysis of 165 studies revealed no significant advantage of one frame over the other. However, they did find advantages of gain-framed over loss-framed messages in persuading individuals to comply with disease prevention behaviors. On the other hand, for messages advocating disease detection behaviors, gain- and loss-framed messages did not significantly differ. In two follow-up works the authors examined separately the relative persuasiveness of gain- vs. loss-framed messages encouraging disease prevention behaviors, such as flossing to avoid cavities,[109] from disease detection behaviors, such as taking a breast examination to detect breast cancer.[110] For disease prevention, they found gain-framed appeals to be more persuasive than loss-framed appeals, but only for messages advocating dental hygiene behaviors. For other disease prevention behaviors such as safer sex and skin cancer, no differences were observed. On the other hand, for disease detection behaviors, loss-framed appeals enjoyed an advantage for messages advocating breast cancer detection behaviors, but not for any other kind of detection behavior. For disease detection behaviors the meta-analysis revealed a small advantage of loss- vs. gain-framed appeals for breast cancer detection, but not other kinds of detection behavior (e.g., skin cancer, other cancers, dental problems).

Factor 4: The Origins of the framing effect: classic articles by Tversky and Kahneman

Factor 4, which appears only in the analysis of the last decade, is composed of works by Tversky and Kahneman from the 1980s and early 1990s. As noted earlier, in the literature review section, these works were the first to adopt the term framing, from Prospect Theory.[5,6] The emergence of this factor in the last decade of analysis (2011 to 2020) is possibly due to the need for authors of more recent articles to seek the essential pillars of this theoretical construction at the source. Thus, it is evident that the fundamental works of Tversky and Kahneman remain relevant to the present day. In their 1981 work, entitled Advances in Prospect Theory, the authors introduced the term “decision frame” to refer to the “decision maker’s conception of acts, results, and contingencies associated with a specific choice” (p.453).[5] The authors further state that “the structure adopted by a decision maker is controlled in part by the formulation of the problem and in part by the norms, habits, and personal characteristics of the decision maker” (p.453).[5] In their 1983 work,[17] the authors criticize one of the laws of probability, the rule of conjunction (see more in Dempster and Suppes),[119,120] which became known as the “fallacy of the conjunction”. The authors claim that the representativeness and availability of heuristics can make a conjunction of events seem more likely to happen than one of its constituent events, demonstrated in various contexts, including word frequency estimation, personality judgment, medical prognosis, decision under risk, suspicion of criminal acts, and political foresight.

In another article, Tversky & Kahneman analyze the foundations of rational choice theory and demonstrate that the most basic rules of the theory are commonly violated by decision-makers, concluding that normative and descriptive analysis cannot be reconciled.[18] The authors argue that “deviations from actual behavior from the normative model are too pervasive to be ignored, too systematic to be dismissed as random error, and too fundamental to be accommodated by the laxity of the normative system” (p. 252). In 1991, Tversky and Kahneman published Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice – A Reference-Dependent Model,[19] where the authors present a theory of reference-dependent consumer choice. The theory’s central assumption is that losses and disadvantages have a greater impact on preferences than gains and advantages. Finally, in 1992, the authors developed a new version of the Prospect Theory, called the Cumulative Prospect Theory, which employs cumulative rather than separable decision weights. This new version applies to risk and uncertainty scenarios and allows different weighting functions for gains and losses.[20]

DISCUSSION

Framing effects challenged expected utility theory axioms and the tenets of human rationality of neoclassical economics. At the intersection of economics and psychology disciplines, the works of Kahneman and Tversky are considered key in the development of Behavioral Economics and the authors are considered precursors of Behavioral Finance, a theoretical branch that arises from Behavioral Economics.[122]

It should be expected, therefore, that framing effects would develop henceforth predominantly in the fields of economics and psychology. However, our bibliometric study showed that, from early on, since Tversky and Kahneman’s seminal publications, the main theoretical advancements of framing effects were made mostly in the field of psychology. Most of the articles of the first cluster of our co-citation analysis (“Expanding the framing effect”) were published in journals of psychology by psychologists (see Tables 1 and 3). Furthermore, the other clusters that emerged from our bibliometric analysis indicate that the main areas of application of framing effects lie outside the boundaries of its original economic foundations. The second and third clusters that emerged from the co-citation analysis, communications, and health, respectively, evidence that framing effects have been largely applied to other fields, notably health interventions, media communications, and political science.

So, perhaps the main finding of the current research is that, although its foundations have been set out in the field of economics, the development and expansion of framing effects theorizing seems to have been conducted mainly through psychology scholars in psychology journals, who broadened its conceptualization to other contexts. Further, the two main applications of framing effects were also not in economics or finance fields, but in the areas of communications and health-related treatments.

Our study offers thus an interesting case of a phenomenon that has originated in one area, was developed in another area, and found most of its applications in yet other fields and disciplines, providing an interesting case of a scientific development process. Initially, framing effects were confined to risky-choice framing contexts. Such contexts, as in the Asian Disease Problem, involve the choice between alternatives that vary in risk but present linguistically different descriptions of equivalent options that emphasize either gains or losses, frequently leading to preference reversals. In such decisions, preference should be independent of the descriptions of alternatives, a normative principle that Tversky & Kahneman[18] coined description invariance. Because it violates description invariance, framing research caught a lot of attention and gained momentum in the ensuing years.[3] Scholars extensively tested the risky-choice framing effect with many variations, such as the way risk was manipulated, using between- vs within-subjects designs, applying it to different task domains, changing magnitudes of outcomes and probabilities, etc. Several meta-analyses on research that tested risky-choice framing have shown that the phenomenon is robust and reliable.[7,21,60] Later research also delved into whether individual characteristics, such as demographics,[123] elaboration likelihood,[124] expertise,[125] and numeracy skills[88] moderated the effect. For instance, Peters and Levin[88] found that the effect was larger for people scoring lower in numeracy skills. In these early years of investigation, Prospect Theory was the dominant cognitive explanation for the phenomenon.[3] Notwithstanding, other cognitive theories were proposed, such as Venture Theory[27] and the Advantage Model.[126]

The robustness of risky-choice framing effects encouraged other researchers in other fields of study to investigate whether framing effects apply to contexts where the risk of the decision is subjectively defined, or even when the decision entails no risk, as opposed to when risk can be objectively quantified, as in the Asian Disease Problem. Scholars were keen to investigate whether people’s preferences or attitudes would differ simply by emphasizing the positive vs. negative aspects of attributes, traits, or actions of objects or behaviors. This led to some confusion because, as put by Levin, Schneider, and Gaeth (p. 150), framing effects were “often treated as a relatively homogeneous set of phenomena explained by a single theory, namely prospect theory.”[1] This became problematic when the accumulated corpus of research conducted at that point did not always confirm the framing effect.[3] Levin et al.,[3] in the most important work of the first cluster derived in this bibliometric analysis, disentangled the different types of framing effects, namely risky-choice, attribute, and goal framing effects, and proposed different underlying mechanisms for each, providing more clarification as to why some framing contexts worked better than others. Prospect theory was complemented by other cognitive, emotional, and motivational theoretical frameworks to explain different types of framing effects, such as stimulus-response compatibility,[115] regulatory focus theory,[112,127] negativity bias,[42] and fuzzy-trace theory.[28]

Notably, one of Levin et al.,’s[1] typologies, goal-framing effects, in which a persuasive message stresses either the positive consequences of performing a behavior or action or the negative consequences of not performing the behavior or act, gained momentum in scholarly research aimed at finding message frames that maximized people’s engagement in health-promoting behaviors. This stream of research was so important that it stood out as one of the clusters of this bibliometric co-citation analysis. Meyerowitz and Chaiken[42] were the first to use goal-framing to investigate what type of message is more effective in engaging women in performing Breast Self-Examination (BSE). This work appeared as the most important one in the first period of analysis. They showed that information stressing the negative consequences of not engaging in BSE was more effective than information stressing the positive consequences of engaging in BSE. However, the superiority of negatively framed messages was not unequivocal in many subsequent studies, as evidenced in O’Keefe and Jensen’s meta-analyses.[109,110] The ambiguity of goal-framing results led scholars to explore more closely boundary conditions and explanations. In this regard, Rothman and Salovey were two eminent scholars, appearing more in the second period of analysis. Based on the results of their own research,[26,82,106] they proposed a “matching” hypothesis to resolve the ambiguity, in which gain-framed appeals should be more effective when targeting behaviors that prevent the onset of disease, whereas loss-framed appeals should be more effective when targeting behaviors that detect the presence of a disease.[107] This explanation is consistent with Higgins’s regulatory fit theory,[112] and it is not by chance that these papers have been extensively co-cited in the second period of analysis in this cluster.

Framing effects also caught the attention of scholars in the fields of communication and political sciences. Interestingly, in these fields, equivalency framing, that is, the requirement that alternative options or decision scenarios must be equivalent,[3] was relaxed. In political and communication research, scholars rather investigated the effects of political or media discourses which emphasize only a subset of potentially relevant considerations that cause individuals to focus on these considerations when forming their opinions.[74] In a recent literature review, Kühberger[3] called this emphasis framing. For instance, in the examination of the influence of political news on viewers’ attributions of responsibility for political issues, Iyengar[119] manipulated episodic vs. thematic coverage by having participants watch either a news report that described the financial woes of an unemployed autoworker or a report that juxtaposed the national unemployment rate with the size of the federal budget deficit. This manipulation is a departure from equivalency framing because the two conditions are not equivalent.

This departure was apparently not driven by negligence or misunderstanding from the authors of this field, but rather an adaptation to the purposes of analysis of political discourses, as recognized by Druckman:[71] “Political scientists and communication scholars use a relaxed version of this definition that better captures the nature of political discourse” (p.1042). To illustrate this, Druckman[71] showed how two different political discourses influenced people’s opinions on assistance to the poor. A humanitarian framing focusing on how increased assistance would ensure help for the poor led to greater support for assistance than a framing emphasizing that increased assistance would result in increased government spending. The high cohesion and densities of this cluster, as well as the lower interconnectedness of this group in the network diagrams (see Figures 1 and 2), are perhaps driven by the fact that this field developed much independently from others because it has adopted a more relaxed definition of framing for its purposes.

Another key takeaway from our analysis is that there were not many differences in the co-citation analyses of both periods. We found the same clusters in both periods analyzed and many of the key articles and authors are common to both periods. Because co-citation analysis is based on cited documents,[30] the small changes in the intellectual structure observed between the two periods suggest that research on framing effects in the last twenty years has remained concentrated in the same fields. In other words, the knowledge base and the intellectual structure of scholarly research in framing effects have not changed in a meaningful way.

CONCLUSION

Our research contributes to the understanding of framing effects by employing bibliometric co-citation analysis to map the intellectual structure of the field, identify prolific authors and their works, and analyze its evolution over the past two decades. Our study underscores the contributions of Tversky and Kahneman, particularly their Prospect Theory and the concept of decision frame, and highlights their widespread applicability across various domains of knowledge.

Moreover, our analysis reveals the concentration of research on framing effects into four major groups, each with distinct focuses ranging from advancing theoretical frameworks to applying them in communication, health decision-making, and revisiting foundational theories. Through this, we shed light on the influential scholars driving advancements in each cluster, such as Irwin P. Levin, Shanto Iyengar, Robert Entman, Meyerowitz and Chaiken, and Rothman and Salovey, who have significantly shaped the discourse and applications of framing effects in their respective fields.

Furthermore, our findings suggest a continuity in the intellectual structure of framing effects over time, with the main themes and influential authors remaining relatively consistent across different periods. This underscores the enduring relevance and impact of framing effects research, both theoretically and methodologically, and highlights its profound implications for social and political contexts. By elucidating these trends and contributions, our study enhances the understanding of framing effects and provides valuable insights for future research and practical applications in various domains.

Cite this article:

Costa TC, Rafael DN, Filho MC. Framing Effect Intellectual Structure Mapping: A Bibliometric Review. J Scientometric Res. 2025;14(1):113-31.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

One limitation of the present research is that our results reflect more the past of the intellectual structure of the scholarly research on framing effects. This is because co-citation reflects the state of the field sometime before, not necessarily how it looks now or how it may look tomorrow.[16] For a more forward-looking picture of the field, bibliographic coupling analysis is more accurate in representing a field’s research front than co-citation analysis.[128] This is an interesting avenue of research for future studies.

A second limitation of the research is that we only analyzed the last two decades, so we may have left out the early years of scholarly research on the framing effect. As a result, we may have overstated that framing effects were predominantly advanced by psychology scholars. As a suggestion for future research, it would be interesting to also analyze the period 1990-1999.

Another limitation of this study relates to the use of citation thresholds used in our co-citation analysis, above which papers were retrieved. Filtering through citation thresholds is needed to limit the data to a manageable size. The decision of threshold or cut-off points is a decision of the researcher. Because we employed a low threshold, some smaller subgroups may not have been identified.

Finally, we offer some suggestions for future avenues of research, based on this bibliometric study as well as reflections on the papers analyzed. First, many theories propose to explain the framing effect, with different approaches and proposals. Examples are the Venture Theory[27] and The Advantage Model,[126] as formal models, the Fuzzy-Trace theory,[28] and the Probabilistic mental model theory,[117] as cognitive models, the Self-discrepancy theory,[127] as a motivational model, among other models and representations. In this study, we observed that some of these theories, such as the Fuzzy-Trace Theory and Risk-Sensitivity Theory,[129] have been investigated.[91,130–132] However, so many other theories cited in this study (as seen in Kühberger,[116] for example) appeared in a few articles. Many of these theories can be complementary, or even better explain certain phenomena, in different contexts. Thus, given the vast theoretical dimension, it is suggested, as a proposal for future studies to improve the theoretical understanding of the framing effect, to use theoretical approaches other than those arising from the studies by Kahneman and Tversky.

Second, framing effect theories can be better used to analyze the pro-environmental behavior of individuals. Understanding the behavior of people when they are subject to decision-making regarding the environment, or how external actions can engage them in favor of environmental causes, is important currently, as we face problems such as deforestation, extinction of animals, incorrect disposal of waste, pollution (air, water, and soil), recycling, among other topics (e.g.).[133,134] In the same line of reasoning, the same theoretical bases can be used for studies involving Social Marketing. Understanding how framing messages or situations can shape individuals’ attitudes about a topic (e.g., quitting smoking, drinking less alcohol, vaccinating, having breast or prostate exams, voting consciously) is fundamental for actions of this type. Different frames can encourage or inhibit individuals to adopt certain behaviors.